Good morning, earthlings.

Welcome back to the Amoeba, the eerie field of flickering orbs haunting the grounds of Unnatural Heritage.

Last weekend, I posted the final installment of Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives—a three-part series about the future, and why it looks the way it does. What began as a simple question of aesthetics (Why does the future glow?) slowly unraveled into a meditation on lost futures and the feeling of progress frozen in time. (Did anyone watch the DNC? Are these feelings now irrelevant??)

I try to keep my posts relatively succinct—to flirt with the outer limits of attention that someone sipping coffee on a Sunday might have to offer. It’s about 10 minutes. There’s always more to say.

Consider this a quick, unauthorized epilogue to that series. It’s the messy, personal scraps that guided the ship but were too big to fit in the boat. The same story, but perhaps more lived and felt. Haven’t gotten there yet? No pre-reading required.

Lights Out

In Part Two, I wrote about my journey to Plumb Beach to witness the annual horseshoe crab migration. As I gushed in that piece, horseshoe crabs are a rare example of evolutionary perfection—a simple design that’s remained unchanged despite 450 million years of planetary upheaval.

Unlike us rookies, horseshoe crabs do not sit and fret about the future of their species. After five mass extinctions, you learn not to sweat it.

We watched the ancient crab orgy for nearly two hours that evening. Eventually, the sun began to set, pulling a half-hearted darkness across the beach. Summer solstice: the shortest night of the year. As we walked back to the car, I picked up a shell lying in the sand, its alien-like legs picked clean by a week’s worth of scavengers. We unloaded at my friend’s place in Crown Heights and I grabbed a CitiBike to Bed Stuy. Tenderly, I placed the shell in the basket, chuckling at how much it resembled the helmet I never wear. (At 31, parts of me are still immortal.)

As I turned the corner onto Malcolm X Boulevard, the high from the beach began to wear off. My mind slipped. I thought about work the next day. The client presentation. Not prepared. The emai—oh for fuck’s sake, the emails.

My stomach grumbled. The fridge was empty. My bed sheets sat damp in the dryer.

I turned onto my street, and as I approached the CitiBike station, I just… kept going. Past the docks, past the red light. Past that fucker in the Nissan honking at me.

The night felt too short. I dragged it out behind me.

I biked through Bushwick, then Ridgewood, then Maspeth. I biked up and down the streets like a game of Snake, covering ground but going nowhere. I watched the miles on the display fall—from 15, to 7, to 3, then to 1. I pushed past the warning message, the relentless alerts on my phone. The screen flashed low battery for about a mile before it glitched. The electrical assist turned off on Eliot Ave, and I slammed my quads down in defiance. As I turned the corner on 64 St, the pink glow above the basket began to flicker. Two blocks later, it blinked and fell black.

I dragged the fossilized e-bike a quarter mile to the nearest station and walked the rest of the way home.

Fall from Heaven

There’s an excerpt from Rachel Carson, highlighted in The Marginalian, that always chokes me up.

Author of Silent Spring, Rachel Carson was a brilliant oceanographer and one of the most influential environmentalists in modern times. She interrogated society’s blind faith in technological progress and raised the siren against the environmental impacts of chemical additives such as pesticides. She was also, by all accounts, queer.

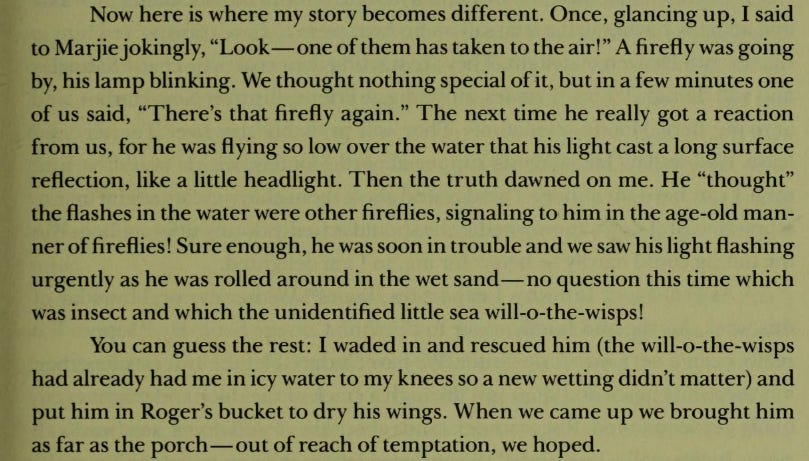

Writing to her beloved companion Dorothy Freeman in 1956, Carson recounts discovering a remarkable display of marine bioluminescence along the beach one night, with “diamonds and emeralds” crashing amongst the surf. As the group watches, one of the embers takes to the sky. A firefly, drifting along the shore.

The firefly floats low above the sand for some time, before suddenly flashing with urgency. Drawn down by the false murmurs of the beach, the firefly becomes captured by the waves and is drawn out to sea.

Rachel jumps in just in time to save it, sheltering it until its wings are dry.

[Title TBD]

How do you imagine your future?

No seriously, I’m asking. Like, what is your process? How do you turn your hopes for yourself into a discernible shape—some blurry map with which to navigate? Do you use a practice or ritual of some kind? Writing? Dreamboards? Perhaps you hazily sift through unspoken desires in the shower every morning, not minding if one of them slips down the drain?

I have ambition—I know I do. But when asked to conjure some clear idea for my future, I feel as if I’m in a dream where I can’t speak.

The convenient milestones set by education have expired for me, and the starter pack for adulthood—house, marriage, kids—feel out of reach and vaguely claustrophobic. Actually, no—cozy, maybe? No, no. Claustrophobic.

If you ask me about the present, I’d say I’m immensely grateful, in a way that sometimes scares me. Things are steady, stable, comfortable, bright. I have a cool job in a meaningful profession that I love. It’s a job that, unless padded by frantic Alison Roman recipes and $70 cocktail receipts, threatens to consume my entire sense of self. It’s a profession that cost me $112,000 in student loans to access.

I live with two roommates in a beautiful brownstone with a garden. I’m hemorrhaging savings on rent in a city that taxes the air, eeking out $200 every other month to get my family past their next medical bill. I have a core group of loved ones who support me in the exact moments I’m too stubborn to ask for it, nestled in a queer community that kisses friends on the lips and means it. We’re all struggling to figure out what a meaningful life looks like beyond the heteronormative script. I’ve yet to find a partner—someone to tie me down and lift me up. Someone to spiritually scheme with. It’s probably because I grew up in a house that taught me more about the pitfalls of relationships than the potential.

It feels like there’s a fence sometimes—this barrier to dreaming that I can’t see over. A giant glacier, perhaps, keeping me frozen in the now. The best I can do is rest my cheek against its surface until it melts just enough for me to take another step forward, into the me-shaped hole that never gets any bigger. Wait, is this a tunnel?

I will say: writing is helping.

Tenebrism and the Glow

The motivation for my series on the future was to answer a simple question: Why does the future glow? To be honest, I’m not sure I ever really got there.

What I can say about the glow is that intensity matters. There is a point where the glow, if too hot or too bright, gives way to something else. Glint becomes glare. Ember rages into forest fire.

Last year, Metrograph organized a retrospective entitled “Neon Noir”, featuring classic cyberpunk films like Blade Runner, Ghost in the Shell, and The Matrix. The films highlight what critic Yasmeen Khan calls “the technicolor tenebrism of modern-day consumerist society.”

If you’re not familiar (I wasn’t), tenebrism is an artistic term used to describe dramatic lighting, in which certain aspects of a scene are highlighted while others lay obscured in shadow.

If you’ve ever been a literal deer in headlights, you know that a bright, sudden light overwhelms the retina, leaving everything in its periphery drowned in darkness. I think this is the danger with certain visions of the future.

The dominant cultural narrative casts technology as the sole hero in our salvation, obscuring the potential for other possibilities. This singular obsession makes for bad technology. The tragedy of living in the spotlight is that it’s too bright to see the humans in the audience.

There are other futures available. Ones guided by social ties, political reform, and ecological wisdom. As Mayan artist Cheanie Noai writes, “flying kites to build a bridge.”

We live in a time where the neon lights of Las Vegas have been superseded by the ominous glare of The Sphere, beaming in through the curtains of every luxury suite rendered visible by its panoptic gaze.

In reality, there is great power in moving through the dark. The largest migration of life on Earth happens in pitch black, as zooplankton and countless other tiny organisms rise thousands of meters from the ocean’s depths to feed at the surface under the cover of night. It’s why gay people never turn on the overhead lights.

The reason we’re attracted to the glow, I think, is because it signals a path forward in which all possibilities are still in view.

So just be patient. Let your eyes adjust.

“The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be.”

- Virginia Woolf, 1915