Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives, PART ONE

VAPOR | How one company defined the aesthetics of the future

Good morning, earthlings.

Welcome back to Unnatural Heritage’s regular scheduled programming! Today’s piece is a return to good ol’ fashioned long-form journalism, in the form of a three-part series entitled “Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives”.

It’s a story about the future, and why it looks the way it does, and how one little French company ended up at the center of all of it. It’s a story I’m really proud of, and one I had an absolute blast researching. Today’s piece (Part One - Vapor) is all about neon, the intergalactic traveler hiding in all of our lungs.

But before we get into it: I’ve got something cool to show you. Follow me.

It’s just up here. Watch that stair though, it has a loose nail. Okay, now come through this door. It’s just around here, in the closet. No, there’s room for both of us, I promise. Okay. Now shut the door behind you. Great. Now shut off the light.

LOOK.

Garden Glow Up

When you think about the future, what does it look like?

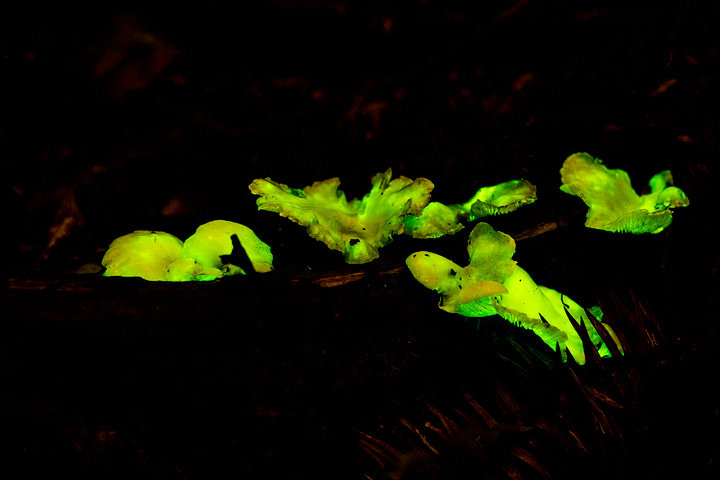

I recently bought some bioluminescent petunias. An Idaho-based company called LightBio cut a little hole in the petunia’s genetic code and inserted a gene from a mushroom called Neonothopanus nambi. The borrowed gene gives the plant the ability to turn caffeic acid into the fluorescent molecule luciferin. And for $29.99, they’ll ship a bouquet of them to your door.

The result is subtle but intoxicating. From my bed at night, the glow is just barely perceptible—the streetlights leaking in and dulling the effect. But a quick trip into the closet, plus a few seconds of visual adjustment, and I am met with the most enchanting green murmur. If I remember to water them, the murmur gets even louder. The brightest bits tend to be the flower buds just before they open—as if the light is a secret they haven’t yet spilt.

The Future is Bright(?)

People tend to have their own visions of the future, but if you ask them what it will look like, you’ll get a lot of the same answers. Robots. Machines. Flying cars with sleek chrome exteriors. Megacities perched above the clouds. Despite having never been to the future, most people’s answers tend to orbit within a pretty consistent aesthetic realm.

If you ask somebody who supposedly is from the future—an artificial intelligence model—you’ll basically get the exact same answers. Ask DALL-E to depict the future and you’ll get overwrought images bursting with hovercraft, drones, and impossibly tall skyscrapers. Even the most quotidian scenes—a group of friends, a birthday party, a garden—if set in the future, end up suffused with the same aesthetic tropes. How do we know it’s the future if there isn’t a robot fairy tending the flowers?

Ultimately, the future exists in the stories we tell one another, and the signifiers of tomorrow regurgitated by AI are those of mainstream science fiction—a genre with a near monopoly over contemporary visions of the future. Despite the narrative potential of stories focused on social progress or ecological repair, it’s hard to imagine a future today that isn’t expressed predominantly through the lens of technology. And it would seem the easiest way to render this technological future is to make it glow.

From control panels and lightsabers to the electric blue eyes of Arrakis, the future is rife with things that glow. When I sit with my petunias in the closet (Happy Pride btw), I certainly feel like I’m in the future. Even though bioluminescence has existed on Earth for millions of years, I can’t help shake the feeling that these flowers are extra-terrestrial. Where does this instinct come from? When did the future begin to glow?

Confined to her house near London in 1915, Virginia Woolf wrote that, “The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be.”

Little did she know that across the channel in Paris, a man named George Claude was working on technology that would redefine the way we see tomorrow.

PART ONE: VAPOR

“The blaze of crimson light told its own story, and it was a sight to dwell upon and never to forget. …For nothing in the world gave [such] a glow…”

— Morris W. Travers

The Prism in Our Lungs

In the late 1800s, a Scottish chemist named Sir William Ramsey made a remarkable set of discoveries. Ramsey noticed that when he extracted oxygen and nitrogen from a sample of the atmosphere, they alone could not account for the volume of gas collected. Somewhere, hiding in each one of our breaths, was something else. In 1894, he managed to isolate a third gas—one that refused to react with the other chemicals in the experiment. He named the gas argon, after the Greek word for “lazy one”.

But it too could not account for the full weight of the atmosphere. Ramsey kept searching, and soon discovered a whole family of gases quietly floating amongst the clouds. Alongside argon, this heavenly lineage included krypton (the hidden one), xenon (the strange one), and neon (the new one)—all descendent from the great Sun, helium. Aloof and unwilling to play with the other elements, they became known as the noble gases.

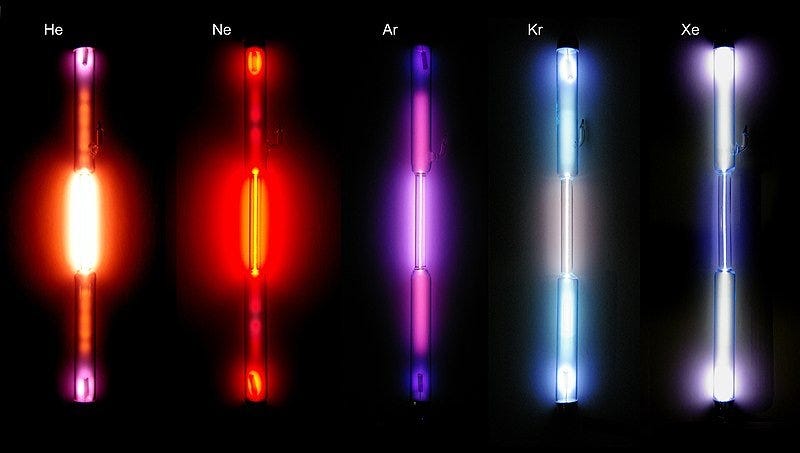

Ramsey isolated these gases in sealed Geissler tubes, exposing them to electrical charges in order to visualize them. Each member of the family glowed a different color: argon emitted a cool bluish-violet, krypton bright white, and neon “a brilliant flame-coloured light, consisting of many red, orange, and yellow lines.”

Of the elements Ramsey discovered, neon turned out to be the most cosmically abundant, ranking fifth in the Milky Way above iron, nitrogen, or silicon. Vast amounts of neon gas can be found swirling around distant stars, softly glowing in the wake of their stellar radiation. But on Earth, neon is relatively rare—a galactic trace in the atmosphere present at only 1 in 65,000 parts. Despite this, small amounts of it still enter your bloodstream with every breath. Inert and unreactive, it passes through your body like an alien observer.

Ribbons of Liquid Light

From the moment it was named, neon was associated with novelty.

The first neon lights made their debut at the Paris Motor Show in 1910—the invention of French engineer George Claude. Claude was a pioneer in the science of air liquefaction—the process of turning gases into liquid by exposing them to high pressures and low temperatures. His company, Air Liquide, began producing oxygen tanks for medical and industrial usage, leaving Claude with an excess of neon gas (a by-product of the distillation process). Inspired by the work of William Ramsey, Claude repurposed the gas to create two 40-foot-long bulbs that lined the motor show’s colonnade in a dreamy reddish glow—a visual symbol of speed and a harbinger of the endless highways to come.

Claude patented his lights and began to build out a market for them. While their fiery red light wasn’t suitable for everyday illumination, Claude saw the potential of their seductive blaze for advertising. In 1912, he installed the first neon advertisement above a hair salon on Boulevard Montmartre. Another sign was soon commissioned for the vermouth company Cinzano, and then for the Paris Opera. By 1914, over 160 businesses had commissioned Claude, including the Moulin Rouge. The City of Lights had been set ablaze.

Soon, the whole world would change color.

Diners, Drive-Ins…

The first neon lights arrived to the United States in the 1920s, commissioned for the Packard auto dealership on 7th and Flower in Los Angeles. The word “Packard” was traced in smart cursive font and outlined by a crisp blue border (achieved by adding mercury to the neon). People drove for miles to see the display of “liquid fire”, and just like wildfire, they spread quickly. Neon signs began to adorn the shops and theaters of Chicago, Pittsburgh, and New York City—inspiring the common adage that “the lights are bright on Broadway”. George Claude set up a subsidiary called Claude Neon and business skyrocketed, earning him the nickname “the Edison of Paris”. When his trade secrets leaked, new businesses popped up to fill the demand.

The end of Prohibition in 1933 led to an ecstatic proliferation of signs advertising “BEER” and “LIQUOR”, and in 1934, over 20,000 neon signs went up in Brooklyn and Manhattan alone. At the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City, a neon sign led the way to General Motors’ “Futurama” exhibit, which introduced the public to automated highways and sprawling suburbs. By the end of the 1930s, neon had gone global, spreading through the streets in Mexico City, Shanghai, and Tokyo.

Las Vegas—arguably the capital of neon—got its first sign in 1936, attracting bingo lovers and horse race addicts to the divey Boulder Club on East Fremont. Incorporated in 1911, Las Vegas was barely more than a village in the desert—a tiny outpost in an otherwise barren moonscape. But the construction of the Hoover Dam during the Great Depression brought thousands of temporary workers, many of whom began to settle long-term. The first casino resort was built on The Strip in 1941, and by the 1960s neon signs had become an essential component of Las Vegas’ unique brand of gaudy, experimental architecture.

Neon was far from just an urban phenomenon, however. Carrying forth its early ties with the automobile, neon signs became a defining feature of the roadside diners and highway attractions that defined the 1950s and ‘60s. Neon signs could be produced at massive scales and were bright enough to be seen from the highway, even in the daytime. The post-war economy led to a proliferation in automobile ownership and a dramatic expansion of the interstate highway system. It also marked the beginning of the Space Age and a cultural fascination with extra-terrestrial travel. All these cultural currents collapsed in the Jetsonesque forms of Googie architecture—the emblematic style of 1950s drive-ins defined by its parabolic forms, starburst ornamentation, and glowing neon trim.

Neon Noir

By the late 1960s, the soft glow of neon had become all but synonymous with the aesthetic landscapes of entertainment, technology, and consumption. But by the 1970s, neon’s seductive allure had begun to darken. As the economic malaise of the ‘70s spread across the globe, urban centers began to experience significant disinvestment, as workers moved to the suburbs to escape crumbling infrastructure and rising crime rates. The 1970s was marked by a period of urban decay, and the neon lights of the city—now broken, aged, and flickering—began to take on a much grittier persona.

From the darkened streets of London and New York City emerged the punk movement—a confrontational reaction to the societal failures that had produced stagnant wages, widespread unemployment, and complacent mass-consumerism. By the 1980s, the impulses of the punk movement merged with anxiety around computing technologies, birthing a new aesthetic offshoot called cyberpunk. Works such as Blade Runner (1982) and William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) introduced cyberpunk into the mainstream zeitgeist. Set in the dense, dark cityscapes of the future, both works used neon as shorthand to depict a society oppressed by the toxic glow of corporate greed and excess.

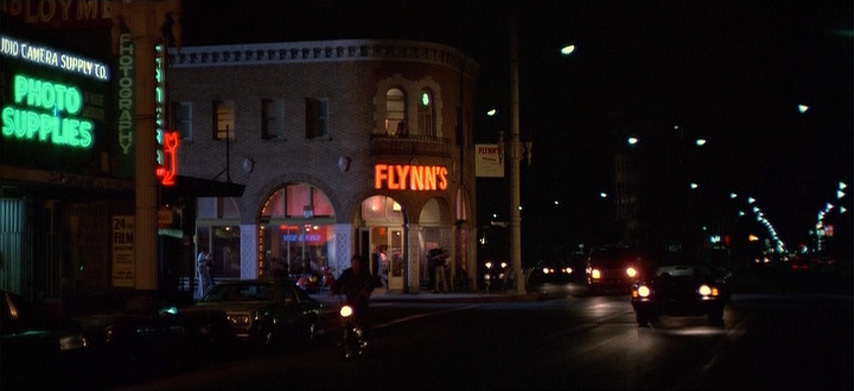

In a way, neon signs introduced the 20th century to the digital interfaces that would follow—prescient physical analogs to the glowing lines and flattened shapes that blinked across early computer screens. These two worlds collapsed in movies like Tron (1982), in which Jeff Bridges’ character journeys from the neon glow of Flynn’s Arcade to the gleaming grid of the digital realm.

These early cyberpunk aesthetics came to define a distinct style for the future that still persists today, in everything from Hollywood blockbusters to DALL-E hallucinations. And while the aesthetics of science fiction have evolved since the 1980s (now trending more brutalist and desaturated), most science fiction still leans heavily on dark rooms bathed in moody shades of unnatural light. Neon itself may have faded, but its afterglow persists.

A by-product of the business of bottling our breath, neon lighting became a key tool in illuminating our digital and galactic frontiers. While its inventor George Claude was arrested in 1944 for his involvement with the Axis Powers (oops!), his company—Air Liquide—would play a vital role in the discovery of yet another important frontier. Only this one was already glowing.

Look out for Part Two of “Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives”, featuring Jacques Cousteau, bioluminescent bacteria, and all of your favorite aliens. Because when the future gets dark, we must make our own light.