Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives, PART TWO

OCEAN | Homo aquaticus and the allure of bioluminescence

Good morning, earthlings.

Welcome to Part Two of “Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives”—a three-part series about the future, and why it looks the way it does, and how one little French company ended up at the center of all of it.

If you’ve got ten minutes, check out Part One: VAPOR.

TL;DR: I bought some bioluminescent petunias off Instagram, and they plunged me down a rabbit hole of asking: Why does the future glow?

From light sabers and computer screens to galactic starships and AI-generated divinations, the only true constant about our uncertain future is that it seems to GLOW—incessantly, and in all manner of unnatural colors. Part One explores this aesthetic axiom through the cultural history of neon lighting, beginning with its invention in 1910 by the Paris-based company Air Liquide. It tracks neon’s journey alongside the major technological developments of the 20th century, following it from Earth’s atmosphere to the marquees of Broadway; from the highway attractions of Route 66 to the gloomy cityscapes of cyberpunk cinema.

“The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be.”

- Virginia Woolf, 1915

My main point: Neon lighting heavily influenced our visual associations around new technologies in the 20th century. As such, the glowing future we’re poised to inherit seems like a relatively new invention—an aesthetic by-product of the last one hundred years of scientific innovation. Before that, according to Virginia Woolf, the future was dark.

Well, at least on land.

Today’s installment dives deep into Earth’s final frontier, exploring how our visions of the future often bubble up from the most ancient of origins.

PART TWO: OCEAN

Last month, I went with some friends down to Plumb Beach near Coney Island. It was the summer solstice and the sun hung languidly in the sky, casually marinating in its longest performance of the year. The moon—not to be upstaged—had arrived early, standing full and proud on the horizon. With a glint of sweat on her brow, she kneaded the tides higher and higher onto the shore, rolling them upwards like a carpet fringed with foam. Just as they reached their peak, the crabs rode in.

Horseshoe crabs. Hundreds of them. Milling about with their armored little bodies. Spewing sperm and eggs across the beach. One of nature’s rare examples of a perfect design, left unchanged for nearly 450 million years. God really ate on that one.

Unlike us rookies, horseshoe crabs do not sit and fret about the future of their species. After five mass extinctions, you learn not to sweat it. Bored with their own perfection, they’ve developed a rich culture of embellishment, each one accessorizing in order to stand out from the crowd. The fashion this year was incredible. Custom-made barnacle prints, clam earrings, seaweed mohawks. Here and there, a corsage of mussels. A masterclass in dressing for an orgy.

Their annual return to the beach highlights horseshoe crabs’ role within the evolutionary avant-garde, boldly negotiating the threshold between land and sea long before the appearance of land animals. Horseshoe crabs were trailblazers of the coastal frontier, no doubt inspiring the lungfish and early tetrapods—shared ancestors of today’s land vertebrates—to finally climb the Devonian shores. While the crabs knew to stay in the water, well protected from the cataclysms above, those other fish-like creatures rose up, developing strange alien appendages like “legs” and “lungs”. Ever since, the ocean has been calling for their return; beckoning them home with soft ribbons of cool blue light. The more intelligent species—the whales and dolphins—plotted their returns early. Humans have arrived somewhat late to the game, returning only as the waters begin to rise around us. But thanks to one little French company, we have learned to regrow our gills.

…and Dives

The same year that George Claude debuted neon lighting at the Paris Motor Show, a young boy was born on the outskirts of Bordeaux. His name was Jacques Cousteau.

Cousteau was a slight, curious boy who developed an early interest in photography, often taking apart cameras and putting them back together. As a young man, he joined the French Naval Academy with dreams of becoming a pilot. Unfortunately, a car accident left him with two broken arms, forcing him to withdraw.

Unable to fly, young Cousteau learned to swim; working out daily to strengthen his muscles. As a teenager, Cousteau had seen the film adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea—the first movie filmed underwater—and he began to experiment with underwater photography. He bought snorkeling gear to fish and to document the underwater landscape, but he was quickly compelled to go deeper. Disappointed with the early SCUBA systems available, he reached out to his father-in-law, Henri Melchior.

Melchior was a director at Air Liquide, a Paris-based company that produced compressed air tanks for medical and industrial use. After hearing his son-in-law’s desire to breathe underwater, Melchior introduced Cousteau to Emile Gagnan, an engineer in the company’s automotive department. Together, Cousteau and Gagnan devised a gas valve system that delivered oxygen according to the ambient water pressure, allowing divers to dive longer and deeper than ever before. With a tube at either side, man regrew his gills.

The duo patented their system in 1943, developing a subsidiary of Air Liquide to sell the invention. The French Navy was among the first to adopt the technology, creating a new division called the Underwater Research Group (Groupe de Recherches Sous-Marin), to be helmed by Cousteau and his friend, Philippe Tailliez.

Cousteau and Gagnan began looking to distribute their SCUBA system internationally, eventually finding traction beneath the neon lights of Las Vegas. Rene Bussoz, an expat and businessman who sold French-manufactured slot machines, signed a 5-year distribution contract to sell the system in the United States.

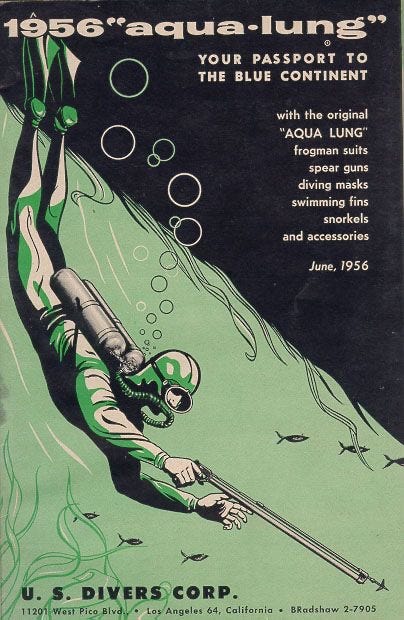

It was the 1950s, and surfing was just beginning to become popular in California. Rather than targeting commercial divers, Bussoz marketed the system for recreation, rebranding it as the “Aqua-Lung” and selling it to young Americans living along the West Coast. He set up a sporting goods store in Los Angeles under the name US Divers and was met with instant success. A new sport was born, and in 1955 Los Angeles County began issuing its first SCUBA certifications. In 1956, Air Liquide acquired US Divers from Bussoz, taking the SCUBA market global.

Suddenly, Earth’s oceans were swimming with a strange new creature.

Beneath the Blue Marble

The Aqua-Lung marked a phase change in the way we understood planet Earth. The stubborn threshold that once separated the known from the unknown was suddenly pierced, revealing a vast blue continent teaming with life. Four hundred million years after our ancestors left the ocean, we had finally returned to it—in the form of Homo aquaticus.

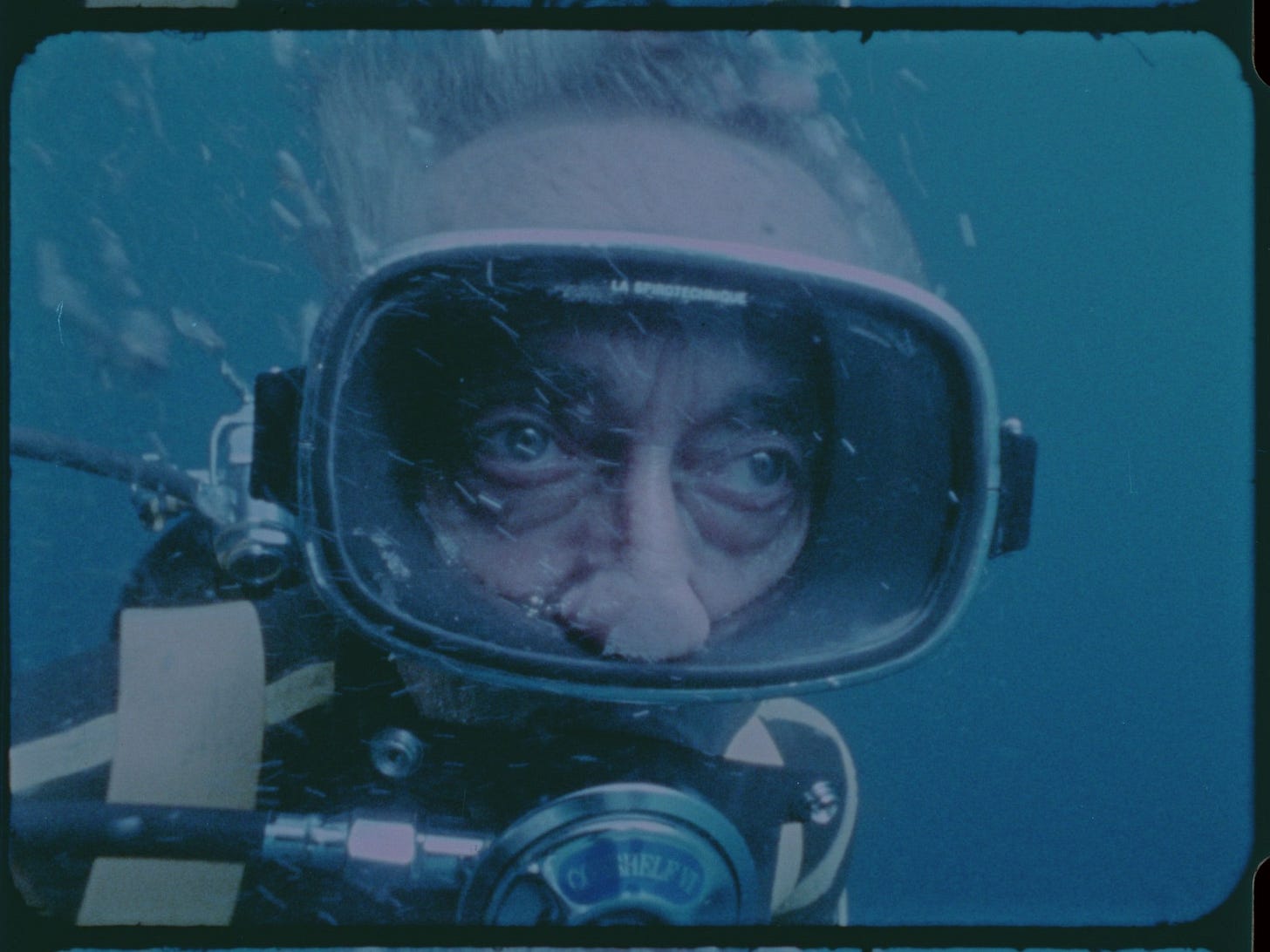

Arguably the most influential oceanographer of the 20th century (and a fashion icon to boot!), Cousteau continued to advance the technology for underwater exploration: inventing his own system of mini-submarines, underwater cameras, and deep-sea field stations. He obsessively filmed his explorations aboard the Calypso, sharing the adventures of his red-beanied brigade in documentaries like The Silent World (1956) and World Without Sun (1964). Both films earned Academy Awards, catapulting the underwater world into the public consciousness (and, in my eyes, defining an enticing new brand of salt-streaked homoeroticism).

Cousteau followed up with the immensely popular television series The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau (1968-1976), innovating new film technology to capture his desired footage. The 37-episode series showcased the rich diversity of ocean life, introducing viewers to never-before-filmed creatures like the nautilus.

Cousteau’s bizarre cast of creatures maneuvered through the dark following strange liquid logics; their bodies sculpted by otherworldly conditions barely imaginable to mankind. Through his captivating storytelling, Cousteau reawakened the notion that life on earth was defined primarily by the logic of the ocean—a reality later brought into sharp focus by Apollo 17’s infamous 1972 photograph, “The Blue Marble”. As filmmaker James Cameron once said, at the height of the Space Age, Cousteau showed the public that there was “an alien world here on Earth.”

The Final Frontier

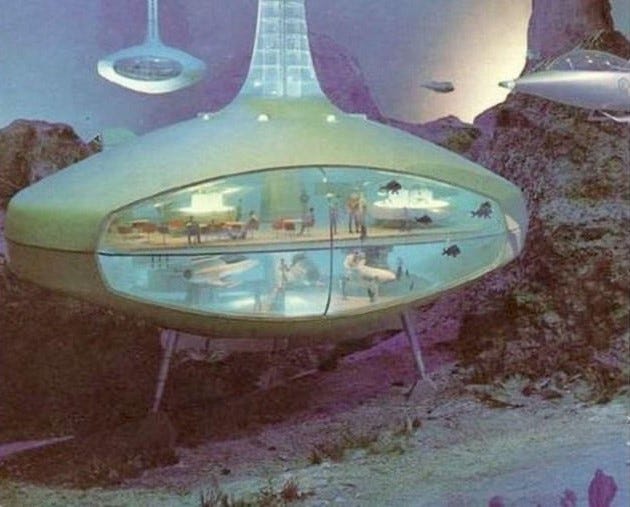

Cousteau’s deep sea adventures rapidly merged with excitement about the Space Race, celebrated as joint efforts to map the unknowns of our home planet and beyond. His Conshelf underwater field stations were seen as counterparts to the lunar station planned for the moon, each inspiring prototypes for future living in General Motors’ Futurama II exhibit at the 1964 World’s Fair.

Following the legacy of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, science fiction began plunging the ocean’s depths for inspiration—egged on by the taut, enigmatic voice of Rod Serling, who narrated both The Twilight Zone and The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau.

As science fiction headed out into space, it took Earth’s alien world with it, using the ocean as inspiration for many of pop culture’s most notable extra-terrestrials. The adult xenomorphs from Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) were purportedly inspired by parasitic Phronima, while the larval “facehugger” form bears a striking resemblance to an overturned horseshoe crab. Similarly, the Shai-Hulud from Dune (1965) pulled inspiration from the predatory, sand-dwelling bobbit worms found in the Atlantic.

Perhaps the most inspiring creatures in science fiction have been the cephalopods—with their ancient, pre-human tentacular intelligence. Cousteau was among the first naturalists to describe this remarkable intellect, in a 1973 book entitled Octopus and Squid: The Soft Intelligence. Cephalopods have gone on to inspire countless alien lifeforms, including the Scramblers in Peter Watts’ Blindsight (2006), the “squid-walkers” in War of the Worlds (2005), and the beloved heptapods in Arrival (2016). In order to visualize the alien in Nope (2022), Jordan Peele actually hired a marine biologist, with the hopes of depicting a creature that “mesmerized its prey like a cuttlefish”.

In some cases, the extra-terrestrial realms of sea and space collapsed entirely, as in James Cameron’s 1989 film The Abyss, which features a bioluminescent form of “non-terrestrial intelligence” hiding out on the ocean floor. The alien scenes in The Abyss are colorful and psychedelic, pulling the cyberpunk aesthetics of the 1980s down below the surface. The Abyss received mixed reviews upon release—the aliens described as both “benevolent angels” come to save humanity and (in a less enthusiastic review) as “Day-Glo Gumbies”. Despite this, Cameron doubled down on the association between bioluminescence and alien life in his popular Avatar films, set on the glowing moon of Pandora.

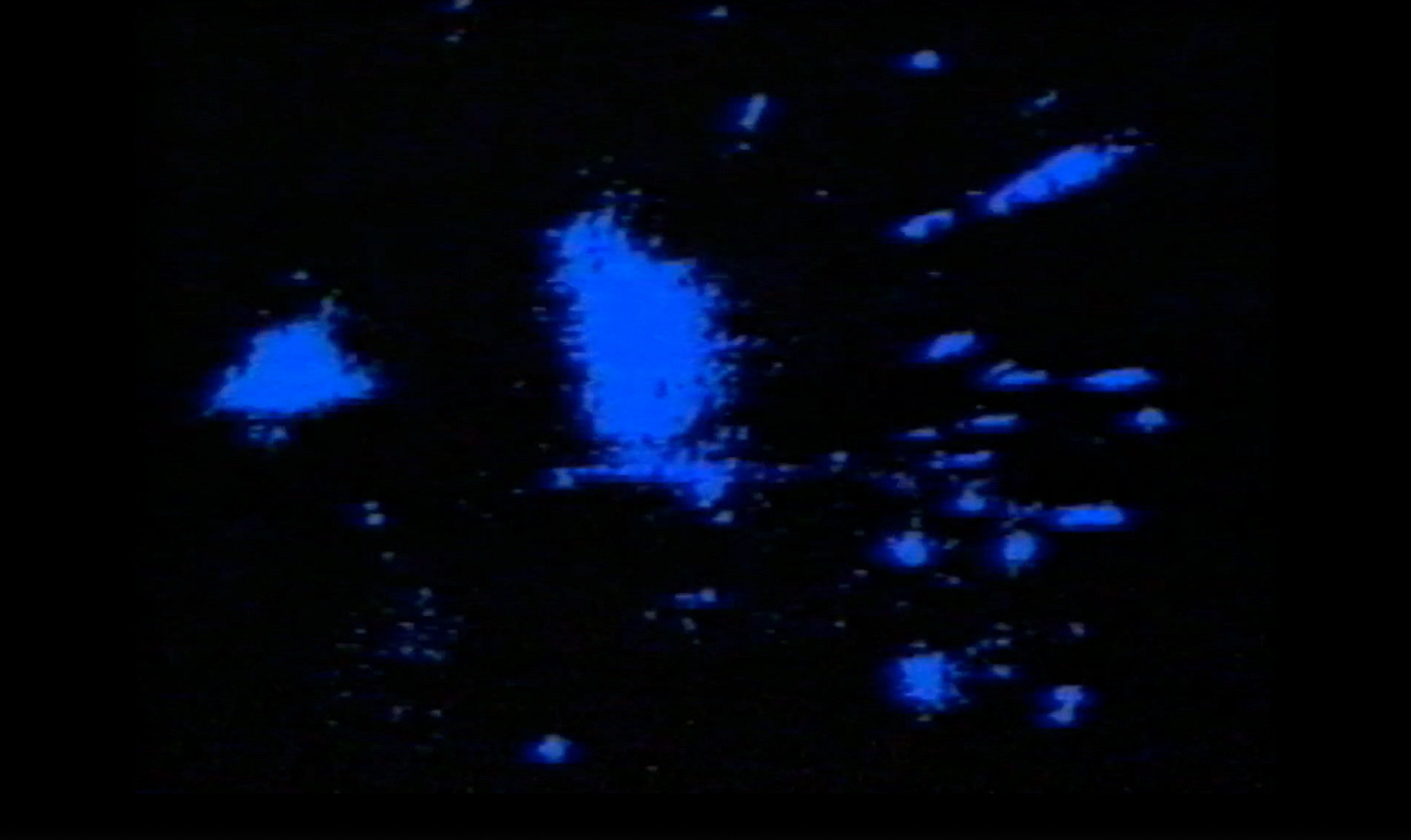

Cameron’s stylistic use of bioluminescence in The Abyss came just as the scientific community was figuring out how to study the phenomenon in real life. While evidence of bioluminescence extended back to ancient Greece, no one had been able to capture it on camera. In 1984, a young PhD student named Edie Widder was taking measurements in her one-person submersible WASP suit when the entire suit was set ablaze. She had drifted into a group of siphonophores that lit up as she disturbed them, flooding her suit with brilliant blue light. She returned on a subsequent dive with a high-sensitivity camera attached to a mesh shield.

As the creatures in the water column hit the mesh, they began to sparkle, creating the first-ever footage of marine bioluminescence in action. The unknown words of an ancient language, finally caught on camera.

The Language of Light

“The reason I love the sea I cannot explain – it’s physical. When you dive you begin to feel like an angel.”

- Jacques Cousteau

When Lucifer fell from heaven, he almost certainly landed in the ocean.

Bioluminescence is produced through the enzymatic reaction between oxygen and the molecule luciferin—Latin for “light bearer”. Thanks to new research, it’s estimated that almost 90%(!) of the species living in the open ocean exhibit some form of bioluminescent signaling—deploying it to lure prey, evade predators, and send warnings to other creatures nearby. An ancient form of communication dating back 450 million years, bioluminescence is perhaps the oldest and most commonly spoken language on Earth, expressed in thousands of dialects across the planet—from fireflies to jellyfish. To see it, we just have to turn off the light.

Even before our ancestors left the ocean, there were octocorals exchanging photons back and forth. And while we failed to evolve such incandescent abilities on land, light is the language by which the ocean still calls to us—a message that, on some level, we still understand. It is the predominant language of our little blue planet, and everywhere, we are drawn to it.

From neon lighting to fiber optic internet, we have unwittingly pursued our own dialects of light, embedding their luminous syntax into our visions of the future in hopes of navigating a way forward. If the future is as dark as Virginia Woolf described (and it certainly seems to be), then it is in our best interest to make our own light.

Look out for Part Three of “Diners, Drive-ins, and Dives”, coming soon! We’ll continue to wax poetic on the topic of bioluminescence, and beat the summer heat with a brief detour into refrigeration and cryogenics. Why, you ask? So we can arrive at the final question: Why do our current visions of the future feel so frozen in time, and how can we light a new path forward?