Good morning, earthlings.

Welcome to the final installment of “Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives”—a three-part series about the future, and why it looks the way it does, and how one little French company ended up at the center of all of it.

Until now, our investigation has been guided by a single question: Why does the future glow? From alien spaceships to digital codestreams, it seems the easiest way to render something "futuristic" is to make it glow. But where does this visual shorthand come from? Why does tomorrow beckon us so?

Part One explores this aesthetic axiom through the lens of neon lighting, charting neon's historic journey in through our lungs and out into our cities, and locating its visual impact alongside the major technological developments of the 20th century.

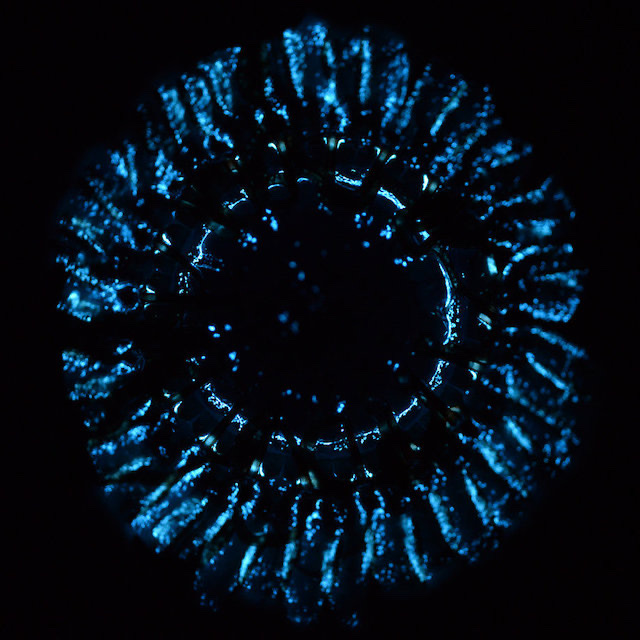

Part Two dives deeper in time, revealing how the ocean became a key source of inspiration for modern science fiction, and exploring the ways that the oldest language on earth—bioluminescence—draws us in with its uncanny, familiar strangeness.

Admittedly, many of the visual references mentioned in those pieces feel somewhat dated today. From roadside diners to cyberpunk cinema, #TheGlow is an aesthetic byproduct forged squarely in the techno-optimism of the 20th century. Attitudes around technology have shifted since then, but its aesthetic impact persists. We seem firmly rooted in this 20th-century imagination—attempting to maintain its optimism amid our more troubled digital landscape. Even the persistence of cyberpunk, with its darker and more pessimistic currents, feels like an attempt to pause the timeline at the exact moment things began to change.

Some folks argue that we've clung so tightly to vintage visions of the future that we've failed to invent any new ones—visions that might define a uniquely 21st-century outlook. The entertainment landscape is bloated with the sequels and prequels of bygone cinematic universes. Science fiction keeps regurgitating the same regressive dystopias. Have we really failed to invent any worthwhile futures?

Part Three is a meandering exploration of a future gone fallow. It’s an inquiry into how our attitudes about tomorrow have evolved—from visionary, to apocalyptic, to avoidant, to…well, hopefully something else.

If our visions of tomorrow really are stuck in the past, then the better question might be: when did the future freeze?

PART THREE: ICE

WARNING: Momentary but lingering doomerism. Stick with me! We'll get through it together :)

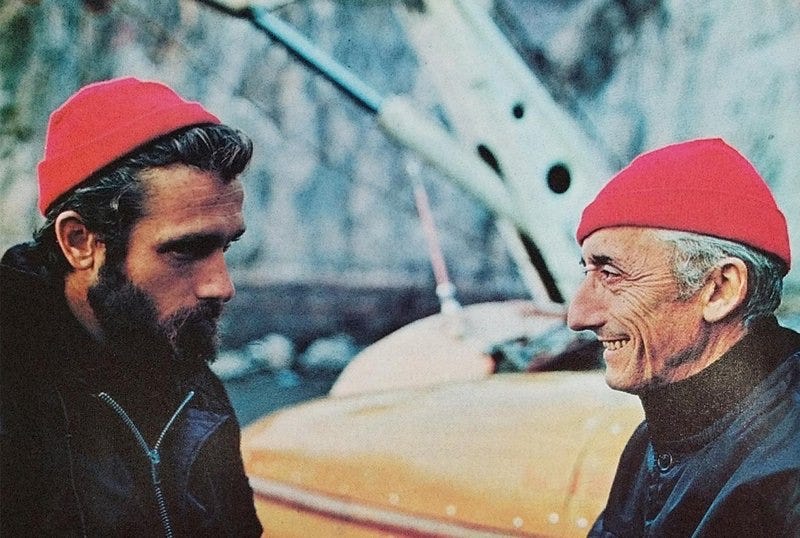

In 1976, Jacques Cousteau released his third full-length documentary, Voyage to the Edge of the World. Co-directed by his son, Philippe, the film depicts the duo's expedition to the Antarctic Peninsula, introducing the audience to vast floating penguin colonies and pale crustaceans with anti-freeze for blood.

"At the approach of these polar waters, we feel alien." - Jacques Cousteau

For much of the underwater footage, there is a strange crackling noise in the background—the sounds of an ice sheet straining under pressure. Halfway through the film, the father and son watch with solemn eyes as a huge portion of the ice sheet calves into the ocean. "We are witnesses to the vanishing of an eternity," Cousteau remarks.

The first World Climate Conference would not be held for three more years, but already, the signs of the climate crisis were becoming evident. Cousteau grappled with his own role in it. The marine expeditions captured in his Oscar-winning first film, The Silent World, had been funded by British Petroleum, with the agreement to conduct offshore oil exploration as part of their research. The crew was ultimately successful, discovering geological evidence of oil deposits in the Arabian Gulf and jumpstarting Abu Dhabi's state-owned petroleum empire. Deepwater drilling expanded rapidly across the globe, devastating the underwater landscapes around it.

As the widespread decline of marine ecosystems became more evident, Cousteau's television programming shifted from wonder to alarm. As a grandfather, he became deeply concerned for the well-being of future generations, and his efforts to inspire environmental stewardship intensified. Saving the world's oceans was an urgent and intergenerational endeavor.

"I am going to work to the bitter end now. That is my punishment."

- Jacques Cousteau

In 1979, Cousteau's son and trusted collaborator, Philippe, died in a plane crash while filming in Portugal. Jacques was devastated. Having lost his son and hopeful successor, his outlook toward the future grew increasingly pessimistic. ABC had already dropped his television series a few years prior, citing its increasingly dark tone. But Cousteau continued to make programming independently. In 1979, he released an episode entitled The Mediterranean: Cradle or Coffin?

The episode begins with footage from an early expedition in the 1940s. The black-and-white footage shimmers with the vibrancy of a reef ecosystem in full splendor. Suddenly, the footage shifts to color. The same reef is shown today: faded, bleached, barren, silent.

Did you know that there’s a hole over Antarctica?

The year of Philippe Cousteau's death, scientists working in Antarctica made an alarming discovery. The concentration of ozone above the continent had plummeted—as if the gods had punched a hole through the heart of the atmosphere. Research revealed that manmade chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), used in aerosols and refrigerators since the 1930s, had begun to seep into the stratosphere, eating the ozone and the vital protection it offered against ultraviolet radiation. Fearing the hole might spread across the planet, scientists and politicians formed the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which laid plans to rapidly phase out ozone-depleting chemicals across industries.

Celebrated as one of the most successful environmental treaties in history, the Montreal Protocol managed to slow and eventually reverse ozone depletion, with ozone levels predicted to fully recover by the 2040s. In addition to protecting humans and agriculture from extreme UV exposure, the Protocol had a second, unintended consequence. The ozone-depleting CFCs used in refrigerators and air conditioners were also potent greenhouse gases. While the Arctic is still predicted to experience its first ice-free summer as early as 2035, studies suggest that the actions of the Montreal Protocol may have delayed this date by up to fifteen years. (Imagine reaching that climate milestone in 2020, for god's sake.)

It's a dark irony of industrial capitalism that our efforts to cool ourselves have accelerated the warming of the planet. Even under agreements like the Montreal Protocol, changes to industry are slow and uneven. Air Liquide—the company that invented both neon lighting and the early SCUBA systems used by Cousteau—was sued by the EPA in 2001 for illegally releasing ozone-depleting aerosols at 22 of its US facilities. While modern refrigeration has replaced CFCs with more ozone-friendly hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), these chemicals are still hundreds of times more potent than carbon dioxide, contributing almost double the amount of greenhouse gases compared with aviation.

Welcome to the Cryosphere

The need for cooling is accelerating, too. Air Liquide (the first company to industrialize the production of liquid nitrogen) has expanded its research and development to include extreme cryogenics—the science of achieving ultra-low temperatures approaching absolute zero (-273°C). Many of the most advanced technologies in development today—from artificial intelligence and genetic engineering to space exploration and quantum computing—require extremely low temperatures to operate efficiently. And while cryogenic systems don't require the same chemical refrigerants as household appliances, they do require exorbitant amounts of energy.

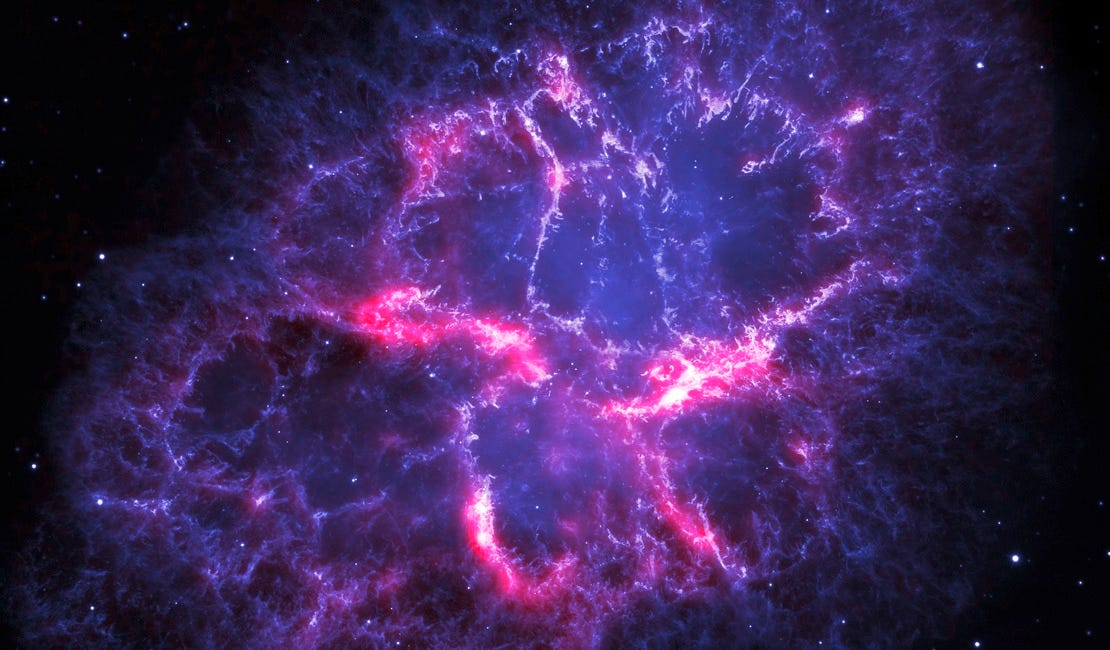

Regardless, Air Liquide continues to shape our image of the future. The company's cryogenic technology is used to store scientific samples aboard the International Space Station, as well as operate the Planck and Herschel space observatories. These two telescopes, which capture high-resolution light and thermal data from the far reaches of space, require extremely low temperatures to avoid thermal interference. Portions of the Planck telescope must operate at just 0.1 Kelvin, making it the coldest point in the known universe.

The planet may be warming, but the technology of the future promises to be exceedingly cool.

How the Future Froze

Though technology is advancing with astonishing momentum, its role as the timekeeper of progress is beginning to erode. The 21st century, and the 2020s in particular, have been marked by a kind of temporal vertigo, in which everything and nothing seems to change all at once. The grand narratives of liberal democracy and technology that propelled post-war culture through the end of the century have begun to fracture, and strange things are crawling out of the cracks. (Ecological collapse, digital fascism, and a global pandemic, to name a few.) At some point, time itself seems to have split along the fault lines, jolting us to where we are now, while leaving other parts of us behind.

The pandemic caused a disconnect between many people’s subjective experience of time and the actual date on the calendar. Graduation ceremonies were delayed years and 30th birthdays slumped by over Zoom. Many people, when asked their age, still pause to calculate. This vague feeling of disorientation, heightened during lockdown, exemplifies a much longer trend in American culture, in which the typical milestones of progress—both personal and societal—have been continually displaced.

To be a Millennial is to feel eternally juvenilized by a system that constantly pulls the future out from under us. The classic benchmarks of adulthood—college, home ownership, children—have been stretched further and further into the distance, like mirages glimmering on the horizon. Each goalpost now comes with a curse: student loans, high interest rates, the specter of an increasingly unstable planet. As the New York Times remarked earlier this year: “It sucks to be 33”.

The displacement of opportunity outward into an unpromised and uncertain future has created a widespread deflation in expectations. There is no longer a common, shared belief that things will continue to improve with time. Society has become disenchanted with the prospects of tomorrow, leading us to take refuge in the exaggerated urgency of the present or the nostalgic comforts of the past. For theorist Mark Fisher, the 21st century has been marked primarily by “the slow cancellation of the future.”

Blame the Arctic Monkeys

As with any societal malaise, the symptoms play out in our art. Fisher cites early evidence for this trend in music, noting how the pattern of decade-defining ruptures in sound characterized by rock n’ roll, disco, punk, and grunge began to disintegrate in the 21st century. Instead, we are in an era defined by historical references: remixes, samples, covers, and (in the case of Beyonce’s Renaissance trilogy) entire tours of established genres.

In his book Ghosts of My Life, Fisher recalls first seeing the 2006 music video for the Arctic Monkey’s “I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor”, convinced it was a lost relic of 1980s post-punk rock. The song is emblematic of the 2000s indie era I grew up in. While it sounded new to me at the time, it was a tour de force of genre revivals—folk (Fleet Foxes, Bon Iver), punk (Fall Out Boy, Paramore), blues rock (The Black Keys), even vaudeville and baroque (thanks, Panic! at the Disco).

For Mark Fisher, contemporary pop culture is simply the experience of having 20th-century culture streamed to you through 21st-century technology. While I disagree that nothing new has been created in the last twenty years, our cultural obsession with nostalgia is irrefutable. The entertainment landscape is bloated with remakes, sequels, and prequels. Science fiction—once at the avant-garde of imaginative optimism—is stuck in a torment nexus of apocalyptic dystopias. And until extremely recently, political imaginations on both sides were dominated by Boomer nostalgia. New stories, while exceedingly necessary, are simply too risky to be profitable.

Fisher locates the origin of this temporal malaise—our sense of having taken the wrong path—in the neoliberal turn of the 1980s. Over the last four decades, neoliberal policies have hollowed out middle-class wealth, economic social programs, and our general sense of collectivism. In Ghosts of My Life, Fisher argues that society is haunted by the lost futures that neoliberalism precluded. The ghosts of these futures now animate every corner of pop culture. The future, rather than a vast plane of possibility, has been hollowed out into a mere aesthetic to be consumed. Retrofuturism—one of a thousand vintage styles to choose from.

Justice for Nostalgia

It’s easy to diagnose nostalgia as a kind of drug or pathology, preventing us from imagining a different future. From the very beginning, nostalgia has been understood as a malady that robs people of their motivation to carry forward. In the old days, it was treated with leeches.

Ironically, the neurological processes that guide future thinking are the same as those that orchestrate memory. It’s an obvious but important notion: we envision the possibilities for our future based on the patterns and likelihood of events in the past. Re-living and pre-living exercise the same cognitive muscles. Given this, I think there may be hope for the “recombinatorial delirium” of remakes and remixes we’re currently trapped in.

Don’t get me wrong: there are languishing, maladaptive forms of nostalgia. Disney adults, I’m looking at you. But we are in a moment where it feels necessary to pause and rewrite the grand narratives of the past—narratives told through the myopic and exclusionary lenses of racism, colonialism, misogyny, and homophobia. Narratives that led us to, well, here.

Faced with a present condition that asserts there is no alternative, we must become a generation of dissident archivists, excavating and mutating possibilities until—click—some strange combination of combinations unlocks something new.

Hitting the Defrost Button

“In winter, we witness the full glory of nature’s flourishing in lean times.”

- Katherine May, Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times

The point of freezing something—whether it’s chicken thighs, human bodies, or the future itself—is to eventually thaw it out. Freezing, refrigeration, cryopreservation—these are all future-oriented practices, meant to maintain the vitality of something until a more desirable moment. Yes, millennials may have the lowest birth rates of any generation—but the egg-freezing business is through the roof. To freeze is to believe in the future.

In the plant world, periods of frost are a prerequisite for future flourishing. The physiological processes of vernalization and cold stratification require plants to undergo an extended cold period before flowering or germination is allowed to occur. This ensures that despite false springs or warming weather, things bloom when they’re supposed to.

In her book Wintering, Katherine May evokes winter as a metaphor for the periods of life that require rest and reflection. It is a season for rumination and tinkering, perhaps towards no particular end. It is the time when farmers leave their fields fallow, covering them with the excesses of harvest to replenish nutrients and fertility. It is a welcome season—a practice of survival. Below the biting winds and raging blizzards, there is a quiet and persistent alchemy at play.

Maybe the first step in imagining beyond the present is to recognize that progress, too, has its seasons. Perhaps now, in this apparent winter of futures, we redefine what progress even means. So that when the warm glow of spring finally grips our senses, we know exactly where we are.

AFTERNOTE

In 1991, after decades of advocacy, Jacques Cousteau led the signing of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, which banned mining and resource extraction in Antarctica for a minimum of 50 years. Signed by 25 nations, the treaty protects an estimated 511 billion barrels in oil reserves from drilling and exploitation.

It’s set to expire in 2048 (: