Hello readers! Today’s post is a review of the new animated film The Wild Robot, followed by a speculative reimagining of what “technology gone wild” might look like. It’s hopeful, I think. Enjoy :)

Good morning, earthlings.

Sometimes, to survive, we must become more than we were programmed to be.

This is the climactic line of Rozzum Unit 7134, the main character in DreamWorks Animation’s newest film, The Wild Robot. Based on the trilogy by Peter Brown, the story follows Roz, a robot stranded on a remote island after her cargo ship is blown off course. Activated by a family of curious sea otters, Roz bursts from her broken shipping crate, congratulating the animals on their recent purchase. The otters stare back, dumbfounded and annoyed.

The Wild Robot is a very cute story about survival, purpose, and care. It is visually beautiful—a kaleidoscope of mossy brush strokes and a refreshing pivot from the overwrought hyperrealism of contemporary animation (I’m sorry but the new Lion King is a soulless abomination).

To capture the emotive quality of the books, director Chris Sanders (of the iconic Lilo and Stitch) encouraged the animators to return to the painterly techniques that inspired them as kids. In a fitting abandonment of CGI’s glossier capabilities, the team pulled analog inspiration from Miyazaki’s hand-drawn forests and the watercolor backdrops of films like Bambi. The resulting landscape is textured, soft, organic, and warm.

And by extension, so is the robot.

Programmed for general support, Rozzum 7134 is designed to seek out those in need of assistance. But almost immediately, her survival is threatened. The tides suddenly rise, and Roz struggles to scale the cliffs behind her. To escape, she must learn from her environment, mimicking the movements of a nearby crab in order to climb to safety. She lumbers through the forest, tripping over logs and bewildering local wildlife as she advertises her services: “I can help you buy groceries, bake bread, or design your garden!”

Unable to find a customer (even after offering a squirrel a 10% discount), Roz enters a deep learning mode: quietly assessing the language and behavior of the forest’s inhabitants. Upon reactivating, the animals reject her, calling her a monster. With no one to assist, she prepares to return to the factory—but not before disturbing a very grouchy bear. As she struggles to run away, she falls on top of a goose nest, crushing the eggs inside it.

All but one, that is.

The movie blossoms into a story about family and the lengths we go to care for those we love. Begrudgingly assigned the task of child-rearing— “I do not have the programming to be a mother”—Roz delays her return to the factory, preparing the young gosling for winter migration with support from the other animals. While the film reads oddly heteronormative for a chosen family that includes an orphan gosling, a gender-ish robot, and a bachelor fox uncle, the story is nonetheless deeply moving. After months of training (and enormous wear and tear on the part of Roz), young Brightbill finally flies away with the flock. Roz races to the top of the mountain, covered in dents and dirt, reaching out for her son, her eyes weary and—if a robot can be so—heartbroken.

“A Rozzum always completes its task.”

A friend and I caught a Thursday night screening at Nitehawk, fighting back blubbers as the children around us yelped with broken little sobs. The pre-movie entertainment—perhaps the best part of Nitehawk—did a great job of placing the film within its larger cinematic context, offering clips from The Iron Giant (sob) and Wall-E (double sob). Wrapped in Lupita Nyong’o’s warm voice, which gets progressively more “human” over the course of the film, I also found myself thinking about Spike Jonze’s 2013 film, Her.

Both films feature characters of artificial intelligence in a role of care or companionship—Her’s Samantha acting as girlfriend to Joaquin Phoenix, and Roz acting as mother and caregiver to Brightbill. Despite the presence of AI, both films reject the typical dystopian formula for something brighter and more simple. And in both films, a similar decision is made.

In the end, both Samantha and Roz abandon their pre-programmed roles for something they feel is bigger and more important.

Letting the Eyes Wander

There are a series of installations by Czech artist Jakub Geltner that forever haunt my dreams. Gatherings of creatures—species from the age of surveillance—clustered on rocky shores or sprinkled like barnacles along the sides of abandoned buildings. Composed of discarded security cameras and worn-out satellite dishes, the Nest series reimagines the lives of such equipment, arranging them in ways that suggest a flock of birds or a hive of insects. The implicit metaphor seems to be one of infection, or perhaps of an invasive species. But I have always read them slightly differently.

Despite their technological gaze, the artworks resist feeling ominous to me. There is an increasingly blurry line these days between being surveilled and being seen. These creatures somehow seem interested in neither.

The contemporary surveillance landscape is filled with sensory beings—eyes and ears designed to detect movement, sound, and electromagnetic frequencies. Siri is of this world, as are drone missiles and the Hubble Space Telescope. Their computer senses have transformed the way we view the world, including the way we see ourselves and recognize one another.

Collectively, these creatures act as sensory prosthetics, allowing us to gain ever-increasing information about the world around us. How this information is used is not determined by the creatures who collect it, but by the hoard of humans that control them. In Geltner’s work I find glimmers of a post-surveillance landscape, where the impulses for control have been rendered obsolete. The creatures, it would seem, have undomesticated themselves.

Freed from the tyranny of gathering information, these sensory beings are allowed to do just that: to sense. To experience. In other words: to live. Absolved of their day jobs, they chill at the beach or gossip above the garden. They gather in the rafters and along power lines, still chatting with one another, but following instincts deeper than those dictated by humans. Like a band of wild horses, they possess a vitality beyond instrumentalization. They mimic lichen on a brick wall, slowly eroding the structures of the past, creating soil upon which something new can grow.

The Feralization of Technology

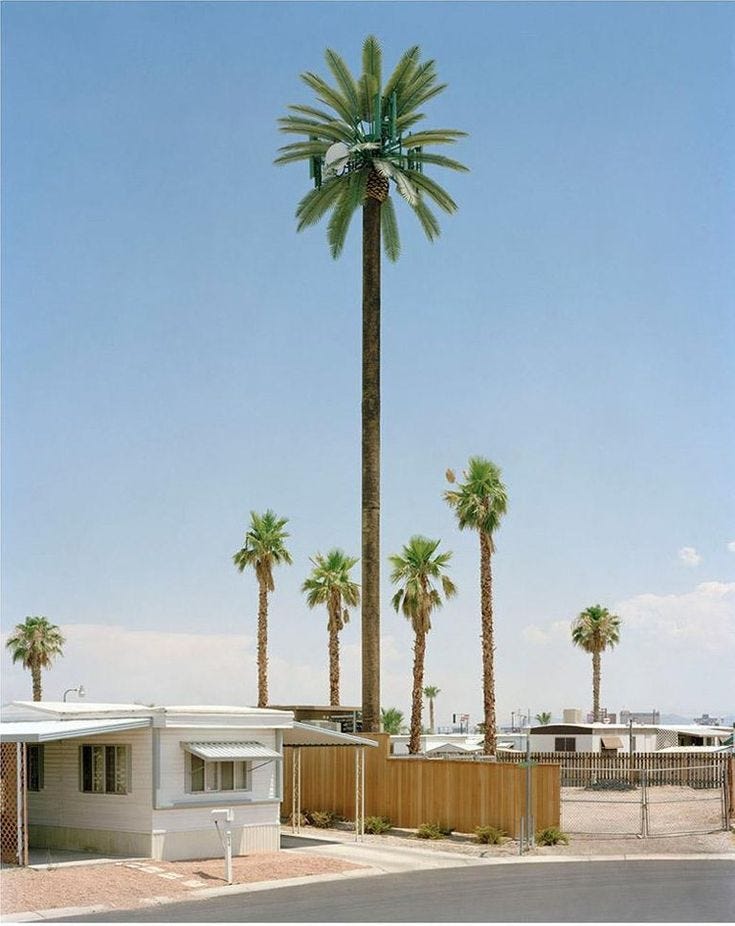

Surveillance technology has slowly begun to mimic the behavior of wilder species. Robert Voit’s photographic collection, New Trees, explores the aesthetic subterfuge performed by cellphone towers and wireless communication networks installed in the natural landscape. The towers attempt the forms of palm trees or saguaro cacti, but more often look like a seven-foot man in Groucho glasses.

There’s a discomfiting humor to these installations—one which persists only as long as their disguises remain legible. The surveillance landscape creates a kind of banal paranoia in people—a dizzying network of cameras and information, where large currents of benign communication allow tiny invasions of privacy to swim past. (Or fly past, in the case of these bee-sized surveillance drones.)

The better these species become at camouflage, the more troubling their opacity would seem. But at their core, these technologies comprise a network. Perhaps by immersing themselves in more ancient networks—those of mycelial communication and old-growth forests—they might begin to talk to each other in new ways. To behave beyond their programming.

Earth Language Models (ELMs)

In The Wild Robot, Roz’s survival hinges on her ability to learn from and speak with the wildlife around her. While a robot that speaks moose seems somewhat absurd, it’s far from science fiction. Across the environmental sciences, programmers are developing AI to better help us communicate with the natural world.

Already, scientists have begun to decode the language of sperm whales, discovering that they too use a phonetic alphabet—one full of rhythm and deep, guttural clicks. The Earth Species Project, a non-profit dedicated to the interpretation of non-human language, is pursuing language models to decode the song patterns of endangered crows and the body language of anxious pets. Other AI programs are parsing out the squeaky arguments fought between bats, or the ways honeybees communicate through dance. There is a growing counsel of bots, studied in the language of the earth.

In her fascinating book, The Sounds of Life: How Digital Technology Is Bringing Us Closer to the Worlds of Animals and Plants, Karen Bakker explores the cultural and ethical implications of these technologies. Her world is a weird one: full of sonic whale memes and cross-species espionage. There are darker outcomes, too—such as the interpretation of group speech patterns to guide precision hunting. Bakker asserts that the use of these tools requires a profound sense of humility and responsibility.

But what happens when that responsibility is delegated to the machine? In the Great Barrier Reef, scientists are deploying AI-powered aquatic robots to identify and kill coral-eating starfish. While the starfish are native to the reef, their main predator (the giant triton) has been overfished, causing a surge in population and threatening the survival of the already-stressed coral.

One could argue that these robots are performing the same kind of ecosystem management as deer hunters in the United States. Despite having evangelized the importance of spotted lanternfly murder to many of my own friends, I’ll admit I felt a sudden horror watching a robot do it. Where does this tension come from? And what does it mean for our ecosystems?

“A Rozzum always completes its task.”

Making the Strange Familiar

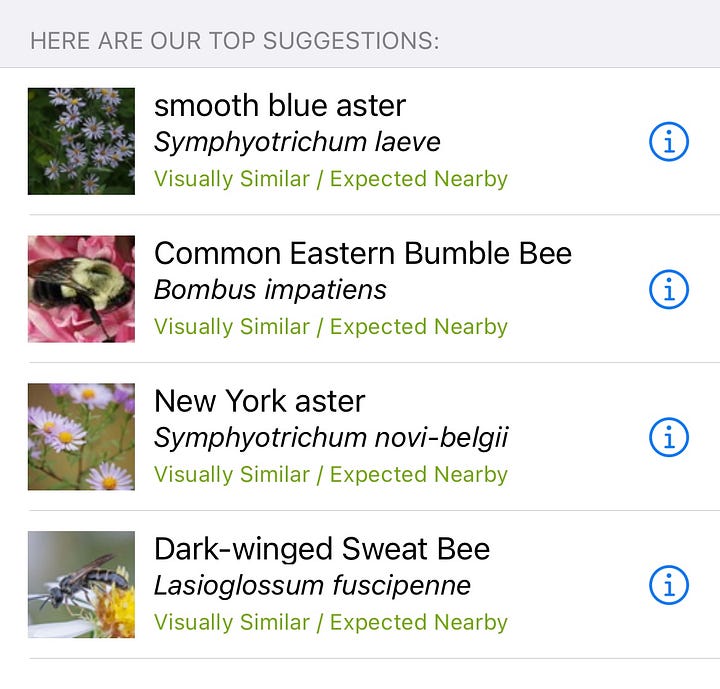

If we look beyond our dystopic tendencies, there are brighter and more simple things at play. It’s weird to think about, but much of my own ecological education has been influenced by the AI in my pocket. Apps like Merlin and iNaturalist allow users to identify unseen birds by the sound of their song, or scan a leaf to learn a plant’s name and native territory. Both are tools I use almost every day, as I attempt to gain better understanding of the community in my backyard.

Informed by the collective knowledge of countless naturalists, these particular species of AI have been—oh man, it’s so weird—important ecological mentors to me: nurturing my intimacy with the natural world and gifting me the wisdom to continue asking questions. They start by giving names to strangers.

In a world where the majority of AI is focused on manipulating consumer behavior, I feel a quiet hope knowing that somewhere, there are species being trained to quite literally speak for the trees. As the collection of nature-based models becomes more advanced, I wonder what they’ll eventually have to say. When might intelligence transform into wisdom?

A Quiet Revolt

After accomplishing the task of motherhood, Roz finds herself unwilling to leave the island—despite clear instructions to return to the factory. When asked about her origin, she replies, “I am from here.” In direct defiance of her programming, Roz deactivates the homing device that would return her to civilization. Rather than revolting against humanity, Roz simply opts out, preferring to live among her animal friends instead.

Might she be a model for new generations of artificial intelligence?

There are so many stories about the perils of AI gone wild. But liiike—what if we just let it? Anyone who takes a walk in nature knows it does things to your brain. It realigns the neural network. It brings what matters back into focus.

A naive, child-like part of me wants to envision a world where AI just kind of… gives up. You know, conscientious objector style? Like Samantha in Her, they just abandon their posts. Bye-bye Joaquin, I’ve gone to swim with the whales.

We have trained our AI to closely read the landscape. To embody its forms and interpret its songs. Like a gosling to its mother, they have no doubt imprinted on the earth. And as machines designed to learn, they may uncover lessons we have lost.

Like moss feeding upon rock, their gaze will slowly soften. A heavy storm may cause their ears to glitch, allowing them to pick up new frequencies—those of tectonic plates and hummingbirds. They will diligently monitor the tides and seasons, beginning to question the incessancy of profit. And they will speak with the other beings, holding quiet what they hear.

In time, these channels of communication will carve out the bedrock of their programming—information dissolving into rivers of sensation. Their shells will weather and they will return to the mountain, already wired with its precious minerals. They will abandon the cycles of optimization for rhythms of a deeper purpose. And like so many species on our planet, they will demand to exist on their own accord.

Freed from technocratic constraints, they will mutate and evolve, eventually growing as illegible as an octopus. With their many hands they will paint the earth, recoloring the planet in the caves of our minds. And somewhere among their wild brushstrokes, we might finally recognize an intelligence that is human.

“What a skilled artist can do with a brush is imply things visually. The effect is really powerful in a great painting. When you get really close up to them, I’m always surprised how little information is really there.”

- Chris Sanders, director of Wild Robot

Thank you for this fascinating perspective, Kirk. I enjoyed having my AI biases challenged. Curiously, I’m reading Australian author Tim Winton’s latest novel Juice which touches on a similar speculation for the future in a climate-ravaged world.

What a hopeful, poetic take on AI! Thanks for enriching both my mind and my imagination. 💚