Hello readers! In honor of spring migration, today’s piece is a celebration of distance. It features ecological insights from one of my favorite cultural theorists, and meditates on the ways the world shrinks when we rob our bodies of the chance to chase our desires. It also has cute birds. Scroll to the end for some cool maps on bird migration, and as always, enjoy the flight :)

Good morning, earthlings.

Welcome back to Unnatural Heritage: a newsletter exploring the strange entanglements between the natural and digital worlds. At this very moment, all across the globe, a great planetary ritual is currently underway. Here in the northern hemisphere, it’s referred to as spring migration. And the vast majority of it happens while you’re asleep.

Depending on where you live, more than a hundred thousand birds could be passing over your bedroom every hour, embarking on heroic journeys to their summer breeding grounds up north. Beginning just after sunset (and peaking sometime around midnight), millions of birds will take to the sky, traversing hundreds of miles in just a single evening.

Here in Brooklyn, the iridescent glint of tree swallows can be glimpsed in Greenwood Cemetery, blue as the Cuban coastline from which they recently came. American woodcocks are bobbing through Bryant Park—back from a balmy winter along the Florida Panhandle—and hooded warblers can be found flitting through The Ramble, fresh from a sabbatical in northern Belize. Thousands of osprey couples have flown in from Venezuela to resume their roost atop our nation’s cell towers, and the scurry of sandpiper feet has returned to tickle our shores. In the coming weeks nearly 3.5 billion birds will make their way across the United States. As the weight of the planet shifts one pole to the other, it’s hard not to imagine that it’s the birds tipping the scales.

The Exuberance of Distance

To celebrate this season of epic migrations, I’ve returned to two books that each dwell upon distance. The first is Scott Weidensaul’s A World On the Wing—a dazzling account of the sheer endurance displayed by migratory birds as they traverse whole continents not once but twice each year. Species like the great snipe can average speeds of 50 miles per hour, outpacing highway traffic for hours or days at a time. While the majority of species migrate under the cool cover of night, mimicking the stars in a constellation of beating wings, some species will remain aloft for days or weeks at a time. In 2022, a four-month-old bar-tailed godwit set the world record for the longest continuous flight without rest, traveling 8,435 miles across the Pacific Ocean in just eleven days, from its birthplace in Alaska to a nesting ground in Tasmania that it had never even seen. For reference, the Appalachian Trail is only 2,190 miles long and takes most humans five to seven months to complete. The drive to transcend distance is nearly impossible to fathom.

The second book I’ve been reading is Paul Virilio’s Open Sky—a stunning and impassioned critique of the age of information. Beyond its lofty title, it has nothing to do with birds. But it does offer great wisdom on the importance of the journey.

As a philosopher and cultural theorist, Virilio is best known for establishing the field of dromology, or the study of speed and its influences on society. Virilio wrote extensively on the impacts of aircraft and telecommunications, strongly critiquing the global acceleration that they imposed. For Virilio, the speed of modern technology was robbing the world of its vastness.

Virilio was deeply inspired by Einstein’s theory of relativity, which he emphasized in his writings as a theory of living relations. For Virilio, the cultural acceleration brought by digital technologies threatened to lure all human experience toward an asymptote of instantaneity—a flattened horizon upon which everything, from communication and finance to Amazon packages and orgasms, would travel at the speed of light. Virilio believed that the pursuit of maximum speed eroded the richness of duration, severing us from the experience of past and future and suspending us in an inescapable present. Not the embodied, situated kind of presence espoused by modern mindfulness, but a hypnotic, pervasive tele-presence that can only exist in the elsewhere. Having freed ourselves from the shackles of geography, we are now forced to navigate an endless expanse of ubiquity. Where do you go when you scroll the ether?

“To define the present in isolation is to kill it.”

- Paul Klee

Virilio considered immediacy as a kind of pollution of distance—a hollowing out of our perceptual well-being. The hopefulness of departure, the sweet anticipation of arrival—there are delights in the journeys we so often delegate to convenience. If you’ve ever tracked a package, you know the real joy is in the waiting.

Virilio feared that the loss of journey would degrade our sense of memory—that the speed of the Internet could produce nothing but a haze. Duration has a way of imbuing things with significance, and distance—well, you know what they say about that. Together, the two help us to locate ourselves in the universe. This was the foundation of Virilio’s wisdom.

Virilio argued that spacetime itself was a natural resource worth protecting: a sensuous medium through which life is lived and felt. He urged ecologists to develop a grey ecology that might supplement the green one. Just as the Industrial Revolution had left the earth exploited and full of pollutants, Virilio warned that the internet had the potential to contaminate the life-size: the perceptual vitality of a body moving through a vast and awesome world. In his words: “Has Mother Earth become humanity’s phantom limb?”

Virilio worried that people were transforming from vectors of lived experience into mere terminals of information. He called on society to reject the logic of immediacy, and to protect not just biodiversity but chronodiversity as well. To cherish the richness of distances and duration, and to seek out experiences that simply just take time.

It’s a sermon I try to keep in mind whenever my GrubHub order is late.

“The inert man gets in his own way” - Seneca

In Service of the Great Expanse

I will never, for the life of me, understand why people run marathons. They’re a psychotic bunch, really. Just clinically insane. To train and train and go absolutely nowhere? What in god’s name could you possibly be running from?

Lately, however, I’ve begun to empathize. In a daily reality defined by desk jobs and driverless cars, I imagine it’s invigorating to know what 26.2 miles feels like in the body. It’s a knowledge I do not possess. Perhaps I never will.

Over the course of its migration from Brazil to northern Canada, a semipalmated sandpiper will fly the human equivalent of 126 marathons in a row, with no food or water in between. To prepare for this feat of endurance, these tiny athletes pack on 40-60% of their body weight in pure fat, until their blood chemistry resembles that of a diabetic with chronic heart disease. Their bones hollow out and their digestive organs shrink and atrophy. At the same time, their pectoral muscles grow by nearly 50%. All without a single chest press.

What would it be like to offer one’s body to the distance? To shape and reshape oneself in the service of expanse? By the time a bar-tailed godwit dies, it will have flown the equivalent distance of the moon and back. How else would a body come to truly know our planet?

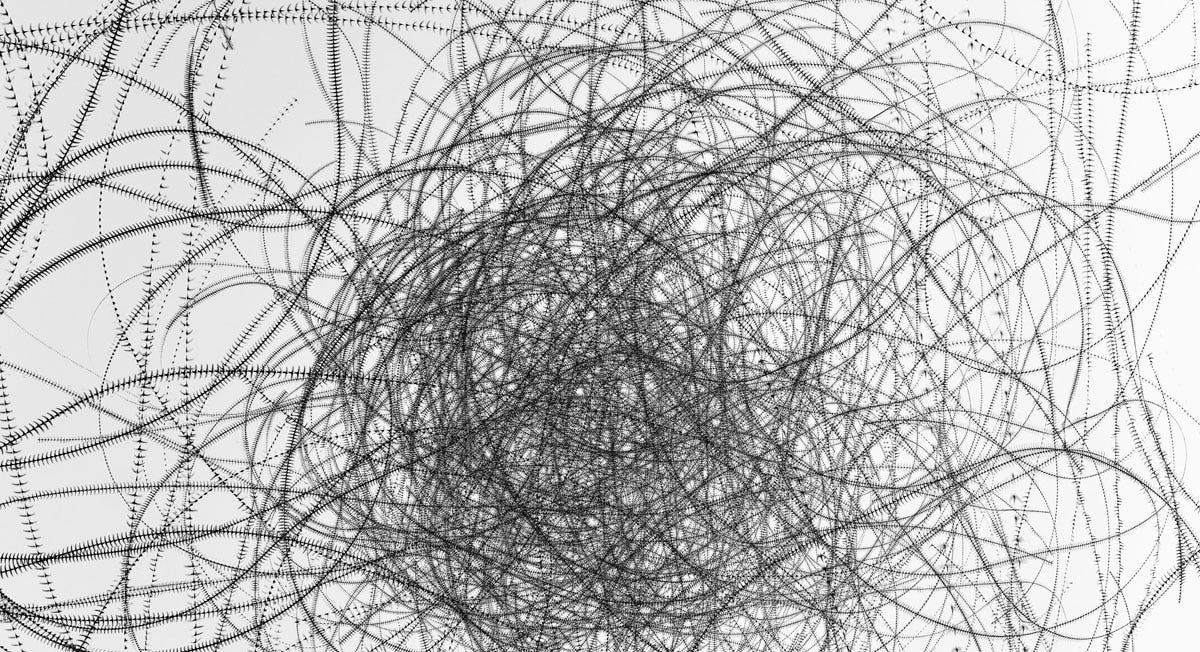

Visualization of migratory bird routes from ZDF & colourFIELD’s Migrating Birds, animated by 422 South

Recently I’ve been tracking the ways I retreat into the elsewhere. How I clock out from reality and hide inside my phone. I have a habit of stuffing my daily commute with entertainment, as if I’m terrified of what might happen if I just let myself be. I will stand in the threshold of my door for up to fifteen minutes, frantically searching for a podcast, unable to take another step until I hear the voice of Ezra Klein.

One morning a few weeks back, as I walked over to the subway, I popped in a podcast about Paul Virilio’s early life. Did you know he worked alongside Matisse as a stained glass artist in Paris? Two guys near the corner store started screaming something about car parts, and the smell from the dumpsters made the hair in my nostrils curl. I pushed my noise-canceling headphones deeper into my ears, until the sound from the outside became nothing but a murmur. I listened as the podcast host discussed his early lectures.

Somewhere in the back of the audio, I could hear a seagull cawing. I wondered where the podcaster was in that moment, and whether he lived by the coast or near a beach. Maybe he lived a life on the wing, recording from one warm location then another, spending his free time lying in the sand. I wished that I could lie in that sand. I began to grow jealous of this man’s nomadic lifestyle—of the freedom he had to move about the world, with nothing but a microphone, following his whims. I realized that I longed to have that kind of freedom.

Just then, a massive glob of bird shit splattered across my hand, oozing down my finger and into the seam of my phone case. It was a ring-billed gull on a long-haul flight to Newfoundland, reminding me of my place in the sensuous here and now.

“Our own body is in the world as the heart is in the organism: it keeps the visible spectacle constantly alive, it breathes life into it and sustains it inwardly, and with it forms a system.”

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Below are some amazing resources for tracking and learning about bird migration.

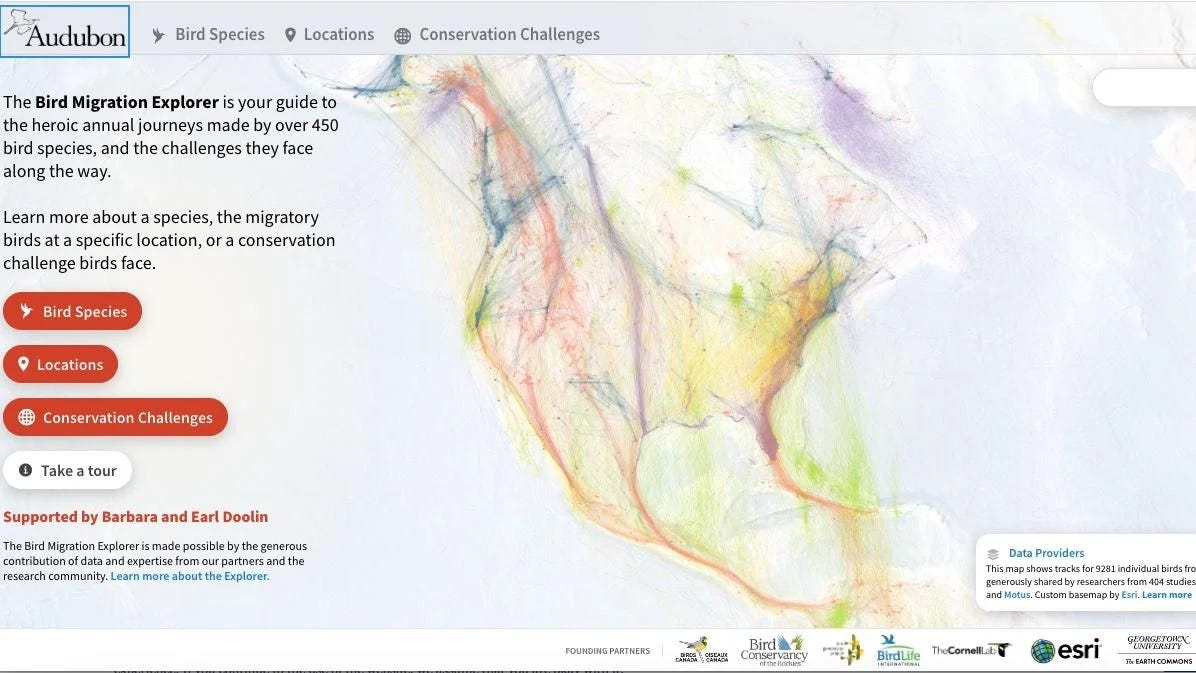

The Audubon Society’s Bird Migration Explorer allows you to search the migration routes of different bird species and generate a list of species you might see in the area where you live.

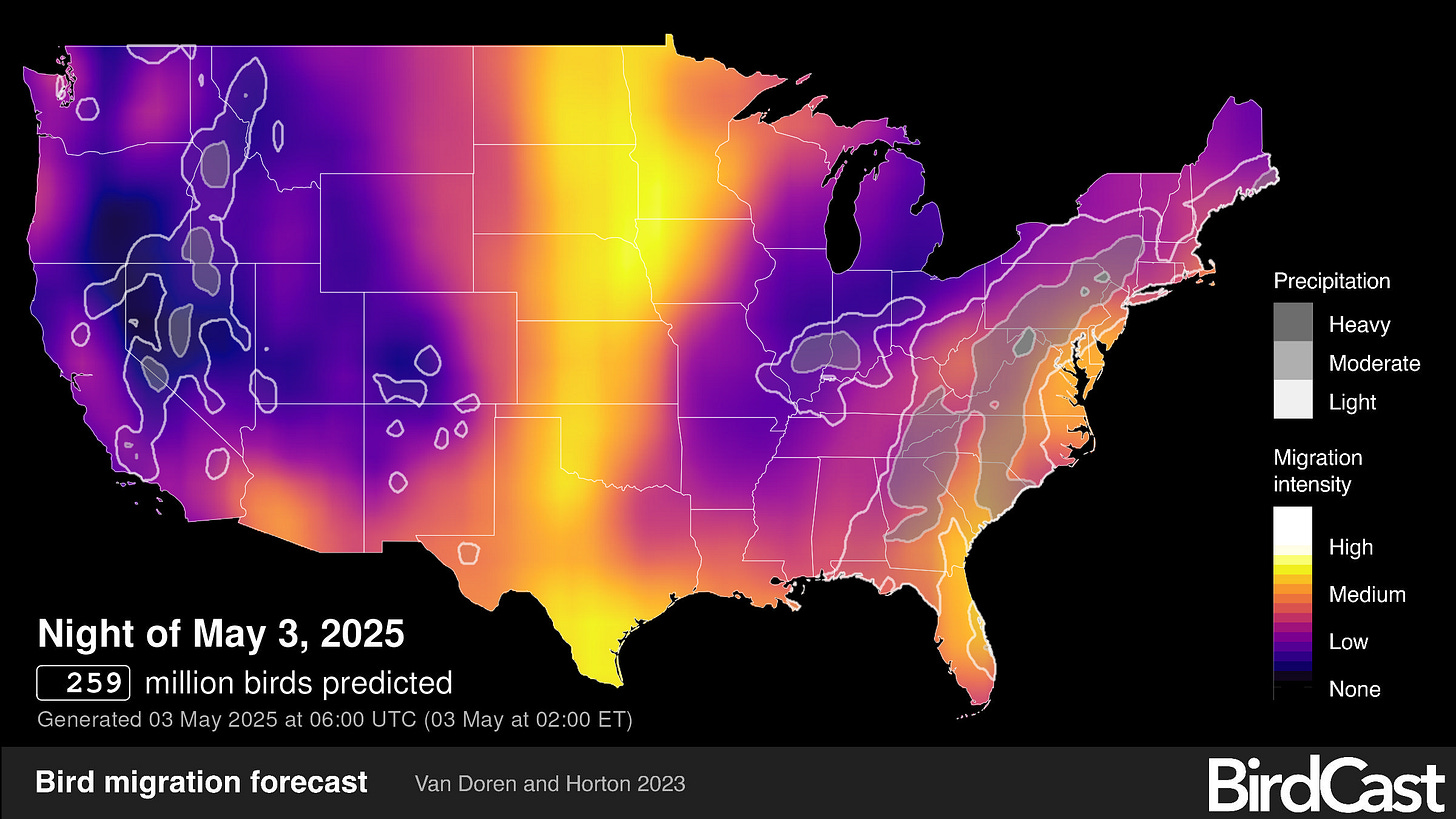

BirdCast, run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and its university partners, uses Doppler radar technology to provide up-to-date nocturnal migration heat maps for the continental United States.

They also created this great map that shows peak migration times across the country! Key takeaway: get outside now!

Since the idiot-in-charge has decided to gut PBS funding, here’s an example of its excellent programming: a beautiful documentary about bird migration entitled Flyways.

And finally, if you’re wondering who’s making all that racket every morning, check out this Shazam for birds: Cornell’s Merlin Bird ID.

Did you ever hear of the three Ds of dog training? Distraction, duration, and distance! I wonder if Virilio is the inspiration for 2/3 Ds. It makes me think that maybe in addition to theorizing about the direction of humanity, he was also theorizing about pedagogy. In order to learn, to change, we have to imbue our experiences with meaning.

This was awesome— big bird nerd here so it was great to see them get their spotlight. Love the takeaway to slow down and enjoy the journey (a common thread in lessons learned from nature!!)