The Nicotine Naturalists Society

Cigarette cards, addiction, and the joys of smoking outdoors

Good morning, earthlings.

Anyone got a light?

—~

I have never been a smoker per se. But like many people in gentle denial of their vices, I’m prepared to admit that I dabble. Enthusiastically, even. A quiet sip of fire beneath the cool cloak of night? Why yes, thank you very much.

Ask anybody: it’s not about the nicotine. I mean, it often ends that way, sure. But before that is the attitude, the connection, the ritual of escape. I started smoking as an excuse to leave parties. Bestowed with a wildly erratic social battery, retreating to the backyard felt much cooler than locking myself in the bathroom, a thousand shower curtain patterns burned into my brain. The scene outside was dignified, intimate, serene even when belligerent. Faces were softer out there, or craggier maybe, whichever—but always so perfect beneath the shroud of electric moonlight. People shared things: cigarettes and lighters, but also names and head nods and breath. Sometimes, two strangers would simply share the silence. In the best moments, the lighter would go missing, and some beautiful person would lean in close and grace the tip of my cigarette with theirs, kissing the night back into existence. And I would lean back, breathing in their blessing, and we’d watch as the flame traveled around like that, an Olympic torch: eternal.

I rarely smoke alone, or during the day. But sometimes late at night, when I’m drunk and evading the devil’s gaze (that is, the orange glow of Popeye’s), I’ll pop into a bodega and grab a pack of Marlboro Lights. If I’m sharing, I’ll get the more democratic Camel Crush, with their soothing, choose-your-own-adventure filters.

A person’s preferred cigarette can say a lot about them. While the cigarette itself suggests a certain relationship with mortality, the brand adds color to this social posturing, conveying the attitude and values one hopes to project. Marlboro Reds, for instance, are usually smoked by people that are trying too hard. Even the way one holds their cigarette can provide insight into their interiority. (Cigarettes, by the way, are perhaps the last object in modern society still held with grace, as opposed to a fist.)

Twentieth-century cigarette advertising pioneered the modes of identity construction via consumer choice that we find so compulsory today. Long before Lululemon moms and finance bro fleece, Don Draper types were marketing cigarettes specifically toward feminists, or housewives, or cool, jazzy black folks. Marketing along gender and racial lines helped tobacco companies tap into large and previously unexploited markets. But early tobacco campaigns went much further than that, targeting consumer groups as esoteric as coin collectors, Egyptologists, and yes, even botanists. While Instagram may seem like some fresh hell of niche, hyper-personalized advertising, I assure you: It’s nothing new.

—~

The Nature of Addiction

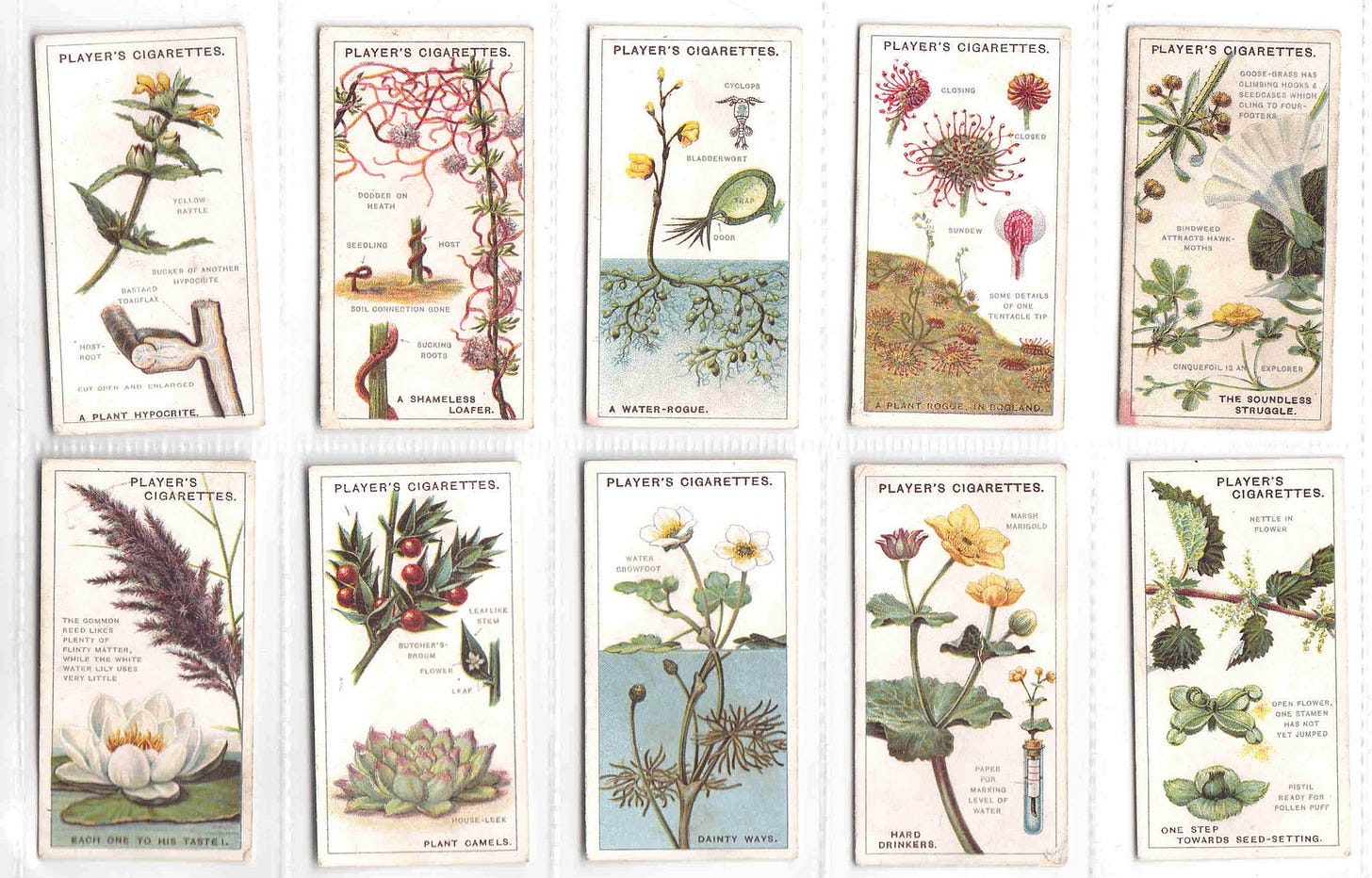

Earlier this year, while frolicking through the fields of Etsy, I came across a set of botanical cards entitled “The Struggle for Existence”. Manufactured in 1923 by the tobacco company John Player & Sons, the cards were inserted into cigarette packs as a way to stiffen the package. Doubling as collector items, each card in the 25-piece set illustrates a different evolutionary strategy of plant survival, titled with kitschy names like “Hard Drinkers” and “Elbow Room, Please!”.

Card No. 1—“A Plant Hypocrite”—details the ways yellow rattle invades the root systems of other plants in order to steal their nutrients. Card No. 3—“A Water-Rogue”—offers microscopic illustration of how the carnivorous bladderwort’s underwater bladders trap crustaceans using tiny trap doors. The other cards depict explosive seed dispersal methods, experiments with root gravitropism, and the sticky adhesives produced by climbing vines.

Needless to say: I was captivated.

The morning they arrived in the mail, I cancelled plans with a friend and sat in my backyard admiring them, Marlboro in hand. The illustrations were stunning and minute, the information fascinating and succinct. After a couple hours (and four or five cigarettes), I had completely memorized them. I knew I needed more.

“Got a fag card, mister?”

-Fred Bason, The Cigarette Card Collector’s Handbook and Guide

The earliest cigarette cards date back to the 1880s and were predictably masculine in theme, depicting beautiful women, athletes, world leaders, and war history. By the 1890s, as more companies began issuing collections as a way to attract return customers, the themes shifted toward stranger titles, like the 50-piece set “Animals in Fancy Costume”.

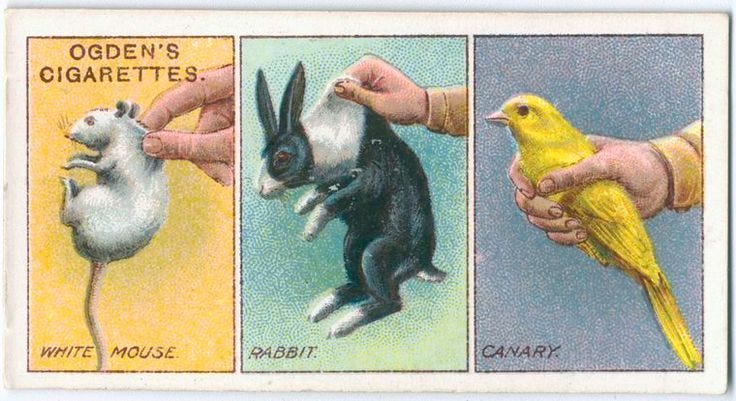

Cigarette card collecting grew in popularity in the 1900s, with children lingering outside storefronts to ask adults for their “fag card”. By the 1930s, the world of cigarette cards was all but encyclopedic, covering topics as wide-ranging as ancient Egyptian gods, famous bridges, Chinese opera masks, common dog breeds, exercise tips, tartan patterns, interesting door knockers, New Jersey history, bassoon lessons, and (a personal favorite) a Boy Scout’s guide to how to properly hold your pets.

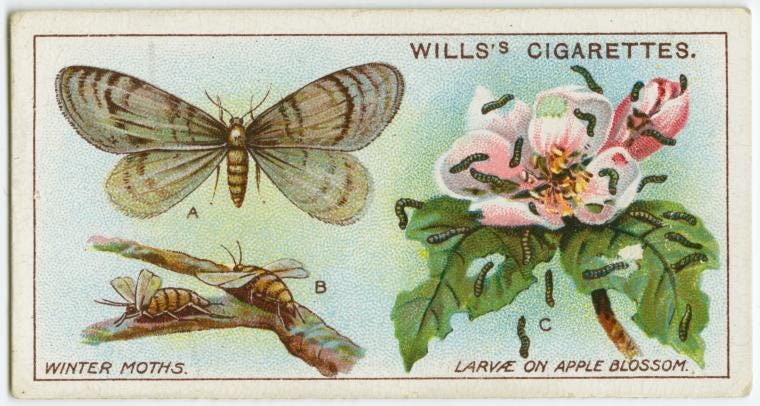

Ultimately, it was the flowers that did me in. Among the first nature-themed collections was “Old English Garden Flowers,” printed by Wills’ Cigarettes in 1911, and followed by “Roses” in 1912. Both sets feature gorgeous botanical illustrations and include brief descriptions of each plant on the back. Wills’ expanded on this theme with 1914’s “Garden Life”, which moved beyond the simple catalog of flower varieties to depict the ecological relationships between plants, pests, and other common garden insects. The cards describe each insect’s life cycle and offer useful tips for dealing with certain pests, often suggesting a mix of natural extracts (though in the case of pesky ant colonies: gunpowder).

There’s a precious, almost mystical quality to these cards, no doubt aided by their diminutive size. Cigarette cards resemble an iPhone in proportion, but at just one-quarter the size, they feel uncanny and slightly bewildering in the palm of one’s hand. Yet they too present a portal to a vast world of information—knowledge that predates the internet and television (and in some cases, even public radio). Eager to uncover their secrets from the past, I began collecting every nature-themed set I could find.

What I discovered was a kaleidoscope of ecological insight—a catalog of the natural world captured right at the dawn of the environmental crisis. Early sets explored topics like whaling, alpine flowers, freshwater fish, roadside wildflowers, butterflies and moths, birds and their eggs, gardening tips, sea shell collecting, flowering trees and shrubs, and (another personal favorite): weird beaks.

Hidden in each illustration are insights not explicitly stated: the preferred host plant of a butterfly larva or the correct bait to use for a particular type of fish. Birds are illustrated immersed in their natural habitats, and the leaves of plants tell subtle stories of herbivory and disease. Technology, too, found its role—as in the exquisite 1929 series “Hidden Beauties”, which documents the cellular mechanisms of plants through the lens of the microscope.

As the decades progressed, the cards also began to tell stories of impending loss, such as American Spirit’s 1980s series, “A Tribute to the Endangered”. The 20th century saw widespread deforestation, the collapse of centuries-old fisheries, and an alarming decline in insect biodiversity at the hands of chemical pesticides. By the end of the century, a documented 543 species had gone extinct, with the undocumented estimation being ten times that. Early cigarette cards bear witness to a natural world that, in many cases, no longer exists in the same way.

Dying For Knowledge

Here’s the point in the story where I admit that I need help. Guys, I’m on eBay every fucking night looking at these things. Every new set is another pack smoked. And sure, I could enjoy them without a cigarette. But it’s a fact of life that some knowledge simply can’t be accessed without drugs. I’m afraid that without the nicotine high, I might miss something.

This is, of course, all part of the plan.

The information sold on cigarette cards tapped into the intellectual culture at the turn of the century, with young men and women gathering for conversation and debate, tobacco pipes hanging precariously from their mouths. Smoking clubs entangled knowledge and nicotine in the same way coffee shops today provide us with a slow, steady drip of caffeine.

But as the North Lancastershire Council Museum points out, it is perhaps the knowledge itself that became the addiction—surpassing tobacco in potency as a form of social currency, and as a means to fashion one’s sense of self and interests. As somebody who embraced smoking as a way to shake the “perfect student” label I’d been slapped with in high school, the world of cigarette cards feels like some kind of cosmic reconciliation—a way to be both nerdy and chic, erudite and cool.

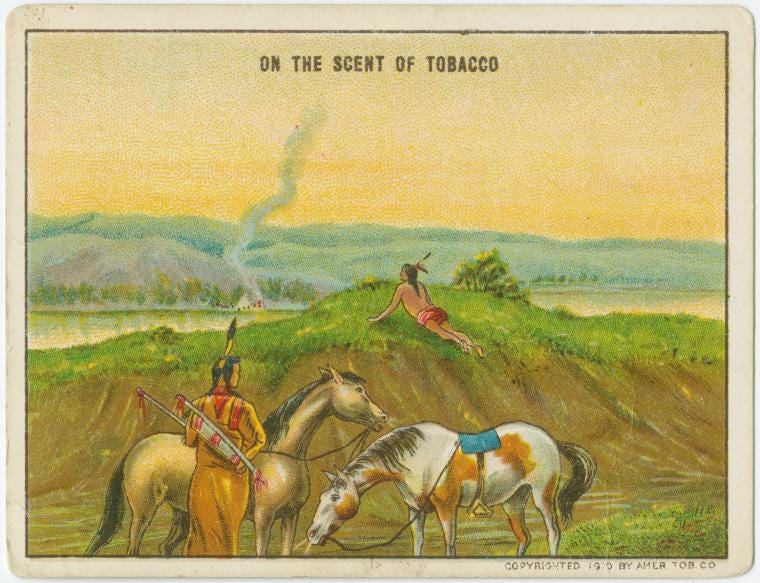

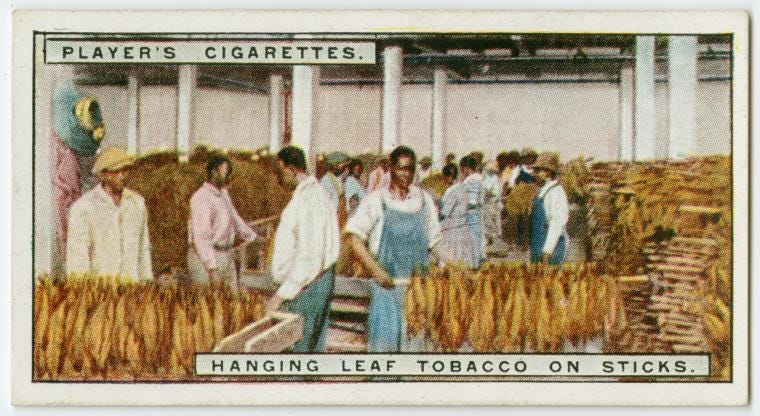

In reality, nicotine is a curse—one which extends out from my lungs and deep into the earth. Tobacco use is responsible for the deaths of over eight million people every year, not to mention the enduring legacy of racism and colonial violence upon which this country was founded—a legacy of plantation labor that decimated indigenous lands, enslaved human beings, and laid rot to the American soul for generations to come.

This legacy is global and persistent: Modern day tobacco plantations clear millions of hectares of forest every year and require more synthetic fertilizers and pesticides than nearly any other type of agriculture. There’s an odd irony here given that nicotine—a powerful neurotoxin—is itself a natural pesticide, protecting the plant from a wide range of insect herbivores.

But we’re not the only ones who’ve developed a taste for nicotine. The tobacco hornworm, which happily feeds on Nicotiana plants, has evolved to sequester nicotine in its tissues, exhaling small amounts of it in an act of “defensive halitosis” that scares off predatory spiders.

Birds, too, understand the merits of nicotine. One recent study found that urban bird species utilize discarded cigarette butts in the construction of their nests in order to ward off parasitic mites.

Other species are simple addicts like ourselves. Hummingbirds and hawk moths will visit nicotine-laced flowers over and over again, ensuring pollination, even if the caloric content of the nectar is much lower than that of other plants nearby. Bees have been observed to do this too, with some studies suggesting that they memorize the color of a flower faster if nicotine is present.

Last weekend, I biked to the park to look through the latest card set that had come in the mail. As I sat there admiring them, I noticed a pair of birds soaring off in the distance. I took a long drag from my cigarette, letting the smoke snake its way out of my lungs, a slight buzz stretching across my temples. I laid back in the grass. The sun was warm on my face.

When I opened my eyes, the pair of birds had flown closer, now drawing circles above the lawn. I looked down at my cards and immediately knew what they were.

P.S. The New York Public Library has an extensive digital catalog of cigarette cards, searchable by theme. Just be warned: there’s no going back!