Good morning, earthlings.

Last May, I organized a group of friends for a field trip to the American Museum of Natural History to check out the newly opened Gilder Center. If you haven’t been yet, the experience is truly remarkable—an organic maze of light-filled portals that reads part human termite mound, part karst cathedral. Once inside, I passed out mushroom candies from my fanny pack and we spread out, marveling at the live leafcutter colony and posing at the interactive bee hive beneath massive globs of honey. The group eventually gravitated around the butterfly diorama—eight large, bearded gay men discussing which butterfly was who with the seriousness of a war room strategy session. After 20 minutes, it was finally settled that I was the Moonlight Queen (Siga liris) and my friend Eamon was the Obrina Olivewing (Nessaea obrinus). We turned around to find a line of frowning children, patiently waiting their turn to have a look.

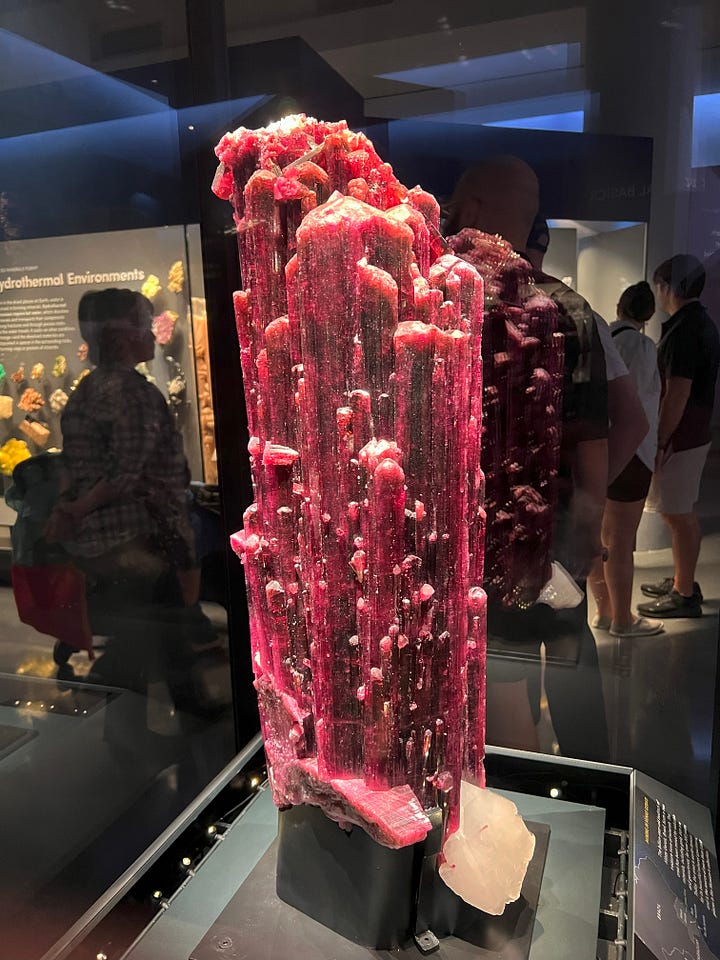

We giggled our way through the museum until we arrived at the most anticipated exhibit of all: the live butterfly vivarium. Unfortunately, I hadn’t realized that the exhibit required an additional ticket, and we were informed that entry was sold out for the entire week. Thanks a lot, Dad. With time to kill, we stumbled our way into the newly remodeled Halls of Gems & Minerals. As we walked in, we let out a round of audible gasps. Greeting us was a massive, glittering cascade of what turned out to be “elbaite tourmaline”—one of the largest intact crystal clusters ever discovered. Like a wine-soaked geyser springing from the depths of the museum, it conveyed such a sense of movement that I questioned for a moment whether time itself had stopped.

With the mushrooms now in full force, we walked around like kids in a candy store, dazzled by the rainbow of crystals and shiny, metallic deposits. Each one seemed to emanate a unique, self-assured sense of character. Pyrite with its solid, pragmatic glamour. Mesolite draped in its delicate furs. Stibnite exuding extra-terrestrial punk rock. There was a strikingly sensual quality to them all. With memories of rock candy in our minds, my friends Noah and Sam and I began to rate them based on their perceived mouthfeel. Amethyst - 8.4/10 - Smooth facets and a hint of suede offer delightful intrigue for the tongue.

We carried on with this game for some time, cackling at the absurdity of becoming jewel thieves simply to suck on them like Gobstoppers. After ogling a particularly delicious-looking piece of malachite, we turned the corner toward the mineral ores display. The mood instantly shifted. We grew intuitively quiet, scanning the shards of copper and azurite with a sense of unease. Unlike the stones before, these ones felt…restless.

We learned that each piece in the display had been sourced from a defunct copper mine near Bisbee, Arizona. As the plaque explained: In 1917 a group of largely immigrant mine workers went on strike; protesting long hours, dangerous working conditions, and dramatically unequal pay. In reaction to the strike, local authorities deputized a posse of townsmen, rounding up the workers at gunpoint and cramming them into cattle cars. Many women and children were rounded up as well. Nearly 1300 people were kidnapped and driven for 16 hours with no food or water. They were abandoned in the desert 200 miles south of Bisbee, with no money or resources. The kidnapping—referred to as the Bisbee Deportation—would mark a key event in American labor history.

My friend Sam’s eyes fixated on a small piece of black and blue Bisbee azurite. “This one is screaming,” he whispered.

The Story Is In Our Bones

Psilocybin aside for a moment—there is widespread, cross-cultural recognition that rocks are capable of storing memories. In Sioux tradition, the powerful god Inyan concentrated his energy to form Ina Maka (Mother Earth), filling her with his spirit and infusing her with his life-giving blue blood. But through this great act of compassion, Inyan became so weak he could barely move. He grew still and hardened to stone. All across Earth, he continues to listen, collecting the stories of his creation.

The stone tape theory offers another interpretation of the capacity of rocks to listen. Popular among ghost hunters, the theory posits that mental impressions created during intense or traumatic events are energetically projected outward, leaving “recordings” in rocks and other objects that can be replayed under certain conditions.

The memories embedded in stone bear equal significance within the scientific community. Our greatest insights into the history of our planet—and about the evolution of life itself—we owe to the world’s stone whisperers. Written in the layers of Earth’s crust are stories of epic transformation. Ancient chemical signatures in lunar and terrestrial rocks tell the story of how the rogue planet Theia crashed into a young molten earth, birthing the moon. Lofty sandstone outcrops sprinkled with marine fossils tell the tale of how the Appalachian Mountains—among the oldest mountains in the world—were once spread wide beneath an ancient shallow sea. And it was the fossilized bones of prehistoric ground sloths that whispered in the ear of a young geologist named Darwin, telling secrets that eventually put God himself on trial.

Geologist Marcia Bjornerud describes geology as a kind of literature, requiring techniques of close reading and thoughtful analogy. Through the careful interpretation of crystalline structures and fossilized remains, encased in deep stacks of granite and sandstone, the archives of earth reveal themselves. For Bjonerud, geology amounts to “nothing less than the etymology of the world.”

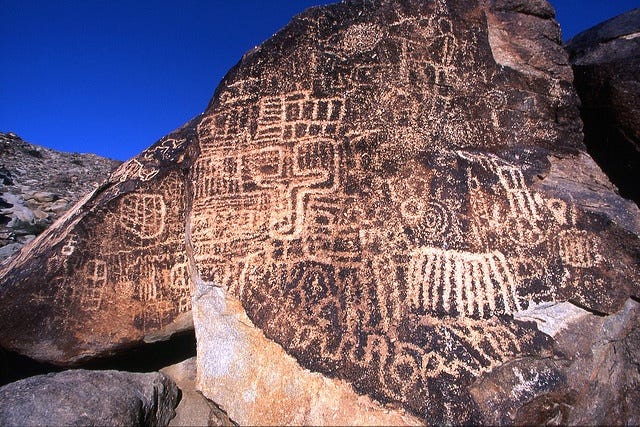

The literary pursuit of deciphering rocks proves significant when we consider how much of human history is actually etched in stone. Over 5,000 years ago, the flows of livestock were first recorded on clay tablets using cuneiform symbols—the earliest form of writing known to man. For 3,000 years prior, the people of the Patagonian desert documented their techniques for survival on the walls of the Cueva Huenel—a cultural history spanning over 130 generations. Ancient petroglyphs throughout the Americas date back even further, depicting elemental symbols of the sun, plants, and animals. The mediums for human storytelling have evolved over time, shifting from rock and metal to, more recently, canvas and paper. But fashion tends to be cyclical, and after nearly 600 years of the printing press, we have somehow returned to making petroglyphs. This time, etched on a silicon wafer.

The Geology of Media

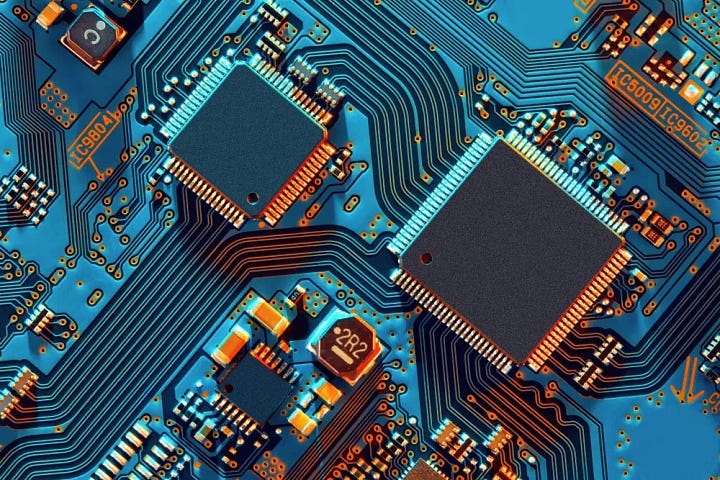

Around 350 million years ago, the African continent slammed into North America, pushing the Appalachian Basin high into the sky. The immense tectonic pressure created by this event forged some of the purest quartz crystals anywhere on Earth. Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, the Spruce Pine Mining District is today one of the world’s largest suppliers of premium-quality quartz sand. Used commonly on luxury golf courses, this sand is also a key ingredient in computer chip manufacturing. Quartz (otherwise known as silicon dioxide) is heated to extreme temperatures to form a perfect silicon crystal, which is then sliced into ultra-thin wafers and microscopically etched to create a tiny electronic circuit. Appalachian petroglyphs, right in our hands.

Compared to other minerals, silicon is especially useful because of its properties as a semiconductor—able to both convey and control the flow of electricity, and by extension, data. Etched into each silicon wafer are numerous memory cells, each storing a single bit of binary data as an electric charge (either on or off). But computer chips are exceedingly complex inventions, requiring the precise regulation of electron flows and temperature variances. Because of this, modern computing requires a veritable who’s who list of minerals to properly function, each selected for its own unique electrochemical properties. The device you’re currently using to read this might contain copper mined in Chile, gold from Indonesia, tantalum from Rwanda, palladium from Russia, silver from Peru, lithium from Australia, and cobalt from the Congo—not to mention stranger-sounding minerals like neodymium and praseodymium, extracted from the depths of the Gobi Desert. A cosmopolitan assemblage of the marrow of the earth, glistening at our fingertips.

Theorist Jussi Parrika refers to this phenomenon as the geology of media. In his book, he charts the scales of deep time that make modern communication possible, elucidating how the foundations of the internet are ancient and geologic. He points out that unlike Saturn’s rings of sand and dust, Earth’s mineral matter takes orbit in the form of satellites and other advanced machinery. This rapidly growing “infosphere”—which as of 2024 includes over 8,300 satellites—bears an uncanny resemblance to the ideas introduced by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin nearly a century earlier.

Taking the Psychic Temperature

Teilhard was a Jesuit priest and paleontologist who rose to prominence for his role in discovering the prehistoric hominid Peking Man. He was an ardent follower of Darwin and wrote passionately about the evolutionary trajectory of mankind. Much like the Sioux, he too placed the origin of man in stone. In The Phenomenon of Man, he charts how the chaotic energy of atoms coalesced into molecules, aggregating further still into minerals and forming the geologic foundations of the earth—the “geosphere”. In the hot chemical soup of this early earth, atoms of carbon began to gather in rings. These rings congregated further, forming complex and repeating shapes that began to self-replicate. From this rocky crucible, the first cell was born, and a new phenomenon enveloped the earth—the “biosphere”. For Teilhard, life represents a revolt against entropy—a cosmic pull toward increased connection and complexity. Through rituals of gathering, individual cells combined to form complex, intelligent, multi-cellular organisms. And in time, a variety of hominids evolved, eventually arriving at Homo sapiens.

At this point, Teilhard is just getting started.

For Teilhard, the dawn of humankind marked a transformation in matter as equally significant as the origin of life itself. With humans, a new phenomenon—that of reflection—encompassed the earth, forming a planetary sphere of thought he referred to as the noosphere. It, too, was influenced by “an eternal propensity to unite”. He wrote how through rituals of gathering, human minds (the cells of reflective thought) have slowly coalesced into tribes, villages, cities, and nations. As the super-organism of the noosphere, culture is able to transcend the capabilities or lifetime of any single person. Teilhard hypothesized that the world’s cultures would continue to exchange ideas, aggregating information and entangling themselves into still greater forms of complexity. Though he died in 1955—sixteen years before the first email was sent—his ideas not only anticipated the internet, but hypothesized what might come after.

Just as the biosphere and noosphere marked inflection points in the history of the planet, Teilhard hypothesized that the complexity of thought—the “psychic temperature” of the Earth—would eventually get so high that a new transformation would take place. This inflection point would mark a moment of cosmogenesis in which a still higher, near unimaginable capacity of matter would be achieved: that of the divine.

Noospheric Turbulence

It is here where I’ll admit that I struggle a bit with Teilhard’s hypothesis. If we follow his lead, the Internet will eventually lead to…God? Hmm. Bumpy road.

But his ideas on the interplay between thought and geology are worth examining. Just as the advent of life greatly altered the chemistry of the Earth, so too has the advent of the noosphere. Much has been written about the Anthropocene: the proposed geologic era characterized by the vast material transformations brought by human activity. Teilhard, too, wrote of the “psychozoic era”—a layer of earth’s geological history marked not by carbon or fossils, but by the “phosphorescence of thought”.

Like the green glow of uranium, our era may be marked by a kind of psychic radioactivity, measured in degrees of decay. In The Geology of Media, Jussi Parikka describes the vast and growing networks of mineral extraction required to support digital technology as a kind of slow violence—a chronic assault on the health of earth’s resources and the systems of life they support. Mining is indeed a dirty business, releasing toxic chemicals such as arsenic and mercury into waterways and poisoning local ecosystems. Vast amounts of land are cleared for mining—including over 1.2 million hectares of Amazon rainforest between 2005 and 2015 in pursuit of gold and iron deposits. Supply chains are difficult to track and labor practices are sometimes brutal. Miners in the Congo—where nearly two-thirds of the world’s tantalum is sourced—are sometimes forced to work at gunpoint, and face the risk of being buried alive by landslides. With the world’s datasphere growing exponentially each year, it’s difficult to understand how Earth’s ecosystems will keep up.

The ethical implications of mining are complicated even further when we consider the nature of rocks themselves. In the projective grandeur of Teilhard’s vision, there is one takeaway that is often overlooked. As both priest and geologist, Teilhard believed that mind and matter were born from the same cosmic material, varying only in “temperature”. Just as the propensity for life already existed within Earth’s geochemistry, so too does the propensity for thought and the divine. Even in the mineral formations of crystal and stone exist the quiet embers of mind and spirit. For Teilhard, consciousness in some form goes all the way down. Inyan is still listening. And talking, too.

The Medium is the Message

If rocks really do contain some small glimmer of thought, what do they gain from remaining so still, so impenetrable? One Native American legend tells the story of how stones were gifted to humans by the Creator to store their sorrow. Knowing that humans would become overwhelmed by the power of their own thoughts and feelings, the Creator offered stone as a vessel strong enough to hold their pain. And so it does, in the form of granite headstones and marble monuments throughout the world. By nature of their steadfast composition, stones serve as Earth’s most reliable record keepers of life.

In her book Gathering Moss, Potawatomi ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer (mother!) reflects on the intimate relationship between stones and moss, describing how rocks, despite their strength and durability, eventually give way to life’s green breath. She recounts finding a moss-shrouded cave while on a hike once, and temporarily losing herself in the language of the rocks.

“My ancestors knew that rocks hold the earth’s stories, and for a moment I could hear them.”

I sometimes wonder if the problem with modern life is that the rocks are speaking a little too much. Our phones are able to deliver us news from around the globe precisely because they are comprised of materials whose purpose is to tell the world’s stories. By means of silicon chips and copper circuit boards, we have greatly accelerated not only human communication but our exchange with rocks as well. We must understand that by communicating through stone, we are inviting them to serve as translators of our conservations, and allowing our thoughts to be influenced by their point of view. Manufacturing a computer chip is essentially taking all the world’s minerals, gathering them in a tiny (tiny) room, and giving them a loudspeaker. No wonder we’re experiencing information overload.

And as the legend above suggests, the information transmitted is often overwhelming. Never before have we had such constant access to the range and intensity of human experience. Joy and violence, narcissism and empathy, anger and melancholy, sexuality and death—all in a 10-minute doomscroll. We are not equipped to process such an immense barrage of emotions.

There is a common aphorism in media theory, coined by Marshall McLuhan: The medium is the message. McLuhan believed that the form of a medium embeds itself in the message, creating a symbiotic relationship by which the medium influences how the message is perceived. Our feelings of digital exhaustion are made clearer when we consider that the medium is born from stone. Unlike humans, stones are practiced in reckoning with the seismic events of the world. They have experienced cataclysm and catastrophe across continents and eons, and have survived things we can only dream of. We are co-communicating with much wiser and more powerful beings. You can annihilate a land and its people, but the rubble of Gaza will not forget. Perhaps this is the great strategy of consciousness without life—it cannot experience death, only transformation.

Geologically, we are in an era of immense transformation, characterized in part by a proliferation in geological diversity. As Jussi Parrika points out, the activities of extractive capitalism have brought forth an entirely new catalog of anthropogenic minerals—chemically transforming across industrial processes and timescales found nowhere else in nature. Rocks act strangely when you yank them from their beds. The Singing Stone—a giant piece of copper ore mined from Bisbee and housed at the Museum of Natural History—got its name after fluctuations in humidity caused the stone to begin releasing pockets of trapped moisture, sounding as if it was squealing. We have manipulated rocks into communicating faster than ever, and new rocks are coming online all the time, speaking in their own unique tongues. How might this affect the conversation?

Speaking digitally: It’s a lot to process. But keep in mind that the internet is only thirty years old. From a geologic perspective, we are essentially digital cavemen, carving our little crystal petroglyphs in what amounts to a New Stone Age. It makes sense that everything feels a little barbaric. The Internet represents the latest stage in the evolution of human thought, but growing into it will require us to evolve emotionally and spiritually as well. Luckily, we are in communication with some very wise beings. In the end, even the metaverse will be carved in stone. Until then, don’t forget to charge your crystals.

It used to make me sad that the Hall of Gems and Minerals lost its wall-to-wall carpeted cat habitat vibe, but not anymore