Hello readers! Today’s longform piece is inspired by a recent class I took on the science of dreams, offered by the Strother . It explores the uncanny insights that blossom as we transition between seasons and states of slumber. For if the earth sleeps in winter — does it also dream?

[cw: daffodil slander!]

Good morning, earthlings.

It’s hard sometimes, in the dead of winter, to remember how the sun feels on the skin. How it soaks into the bone, projecting its image onto every cell, turning humans into galaxies. I, too, must be a galaxy—the way I sparkle in the dark, brushing my fingers along the edge of the universe, watching the ripples dance all around me. I thread each ring like the eye of a needle, weaving new worlds into the tapestry of my mind. My arms, outstretched, soak in the light—and I lift up my hands at the news of new fruit. A cool breeze passes and I loosen my grip, letting them float in a halo around my crown. Suddenly, the blood rushes to my head. When it hits my tongue, it tastes like sugar.

- dream journal, jan 12th

Assignment #1: Sleep On the Ground

For most of my life, I have neglected the power of dreaming. Perhaps because the idea of it has never felt clear to me. Does dreaming refer to the earnest articulation of a brighter future, inked onto paper then carved into the soul? Or are dreams just the slippery soup of murmurs swirling around at the back of our minds? Like the first blossom each spring, dreams are ephemeral by nature. By conflating my waking dreams with those born in sleep, I was always worried that the former might melt away, just as the sun was rising.

Last autumn, my friend Patrick came over to help me plant bulbs in the garden. I’ve been pretty headstrong about only planting natives thus far, stubbornly championing their beauty over the typical, showier imports. But in New York, I must admit: most of our natives are notorious for sleeping in. The first few springs I just paced around the garden, antsy and impatient, screaming at the columbine to WAKE UP, you idiot! It got a bit aggressive. So two years ago, I caved and bought some tulips.

Before the tulips, the only bulb in the garden was a lone daffodil planted by the previous tenant—somebody else’s dream for the garden. Personally, I hate daffodils. Stupid, plastic-looking flowers, with their dumb little duck faces, always weaseling their way into saccharine portraits of lambs and baby bunnies, forcing us to breed and buy shitty chocolate. They’re sellouts! Golden retrievers! The basic bitches of spring. Snowdrops are elegant, and humble to boot—always smiling down at the soil from which they came. Crocuses, too, seem grateful to have found the heavens, carpeting the earth with a hymn sent skyward. Daffodils, on the other hand, turn their heads to stare straight at you—blasting their trumpets in your face, demanding that you smile. Tulips spread joy through layers of sensuous poetry—daffodils write millennial self-help books titled The Subtle Art of Stop Being Sad You F*cking Loser.

This year I bought crocuses, fritillary and snowdrops. We tucked the crocuses along the path to the fire pit—an idea inspired by the path of yellow crocuses leading to Frank Morgan’s grave. (Morgan, if you don’t know, played the original Wizard of Oz.) I nestled the fritillary in and around the log pile and spread the snowdrops across the “woodland zone” out back.

I call it the “woodland zone” because it’s shaded by a giant tree in my neighbor’s yard. A massive pin oak, and the oldest tree on the block. Anytime I plant anything beneath it, I inevitably hit one of its roots—and while I can’t see underground to prove it, I’d bet a thousand dollars they stretch all the way to Queens.

I tucked a few snowdrop bulbs beneath the spicebush and a few more around the ferns. As I dug near the front of the bed, my knife snagged on something, and I wiggled it around until it came free. Sure enough: a tree root. I looked up sheepishly, apologizing yet again, then tucked my last snowdrop bulb right near the wound.

A month later, the tree was gone.

I am staring down at someone’s blank face. There are no features, just a faint echo in the air. No, wait. A mouth. A jagged circle— a scream that can’t escape. I’m looking for rings but there are none. There’s nothing here. Even the echo… I can’t remember what it’s saying. It’s all fading.

- dream journal, dec 19th

What’s the point in dreaming, if it all just slips away?

Dreaming, it turns out, has a lot to do with what we remember. Having moved past Freudian theories of wish fulfillment and libidinal censorship, modern dream science has shown that dreaming plays an even more expansive role in our daily lives: as a powerful and complex form of memory processing. One that operates under completely different rules from our waking mind.

It’s morning, and I am riding on the back of a squirrel, leaping through the canopy in search of something. There’s lots to do and the energy is frenetic. No one can remember what we’re looking for. Suddenly, we’re falling…

I wake up.

- dream journal, feb 2nd

During wakefulness, memory processing is efficient and task-oriented. The mind is just trying to get us through the day: accessing the memories to navigate our route to work, to remember our colleagues’ names, and to look both ways before jaywalking across the street. Daytime memory retrieval is carried out by our prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for executive functioning and impulse control. As such, memories are accessed in a logical, linear fashion, based on the predictable patterns of the waking world. Drop an apple: it falls to the ground.

During sleep, all that goes out the window. As we enter REM sleep, the prefrontal cortex quiets down and our limbic system—responsible for emotional expression and intuition—starts glowing like a toaster. In the safe stillness of our bedrooms, the limbic system is allowed to play: gathering the memories and emotions from our day, and testing their connection to ideas the waking mind was too busy to entertain. Logical constraints evaporate and our conscious defenses dissolve. The mind floats free from the gravity of the day.

I’m in the kitchen, sipping coffee and reading the paper. I smear a pad of butter across the headlines, scraping it softly until it melts into the page. The letters wriggle and burst from the ground, wobbling slightly until they catch the sun. I bite down—crunch—and they sing in my mouth.

- dream journal, march 4th

Assignment #2: Keep a Journal

It wasn’t my blade that killed the tree. It was a phone call. Earlier that year, a dead limb had fallen down in a windstorm, and I called my landlords to come help us remove it. They grew worried that more branches might fall on our building, and they ordered an arborist to cut them all off. It was an exaggerated assault on an otherwise healthy tree, and it was more than she could handle. She did her best that summer, but with half her limbs gone she slowly grew weak. In the fall, more branches fell, and right before Christmas, they cut her into pieces and packed her in a U-Haul. I watched with grief as they carried her dormant body, and in the brief moments when no one was watching, I smuggled bits of her back to the apartment.

The wood was wet and impossibly heavy, and as I carried it inside, I tried to count her rings. Fragments of memories, spliced and reshuffled—lines of harsh winters next to bands of wet springs. From what I could tell she was over a hundred. A century of growth, tearing at my muscles. A century of life, ripping through my chest.

I toiled for justice the only way I knew how.

When a tree dies naturally, it will begin sending nutrients to its family members nearby, signaling through the soil that its time has come. Fungal neighbors are called into action, and over the following decades, the tree is reabsorbed into the community from which it grew. This, of course, can’t happen in a U-Haul. So I arranged her bones in a pile out back, as the whole apartment filled with sawdust. That night she came to me in my dreams.

It’s dark and warm, and I am a thousand ears spread out in every direction, woven together with fibers of string. I can’t see anything but I feel happy. I can hear people chewing all around me, and I’m comforted. The blood is rushing to my head, and I realize I’m upside down. The sweet scent of pancakes wafts through the air.

- dream journal, oct 3rd

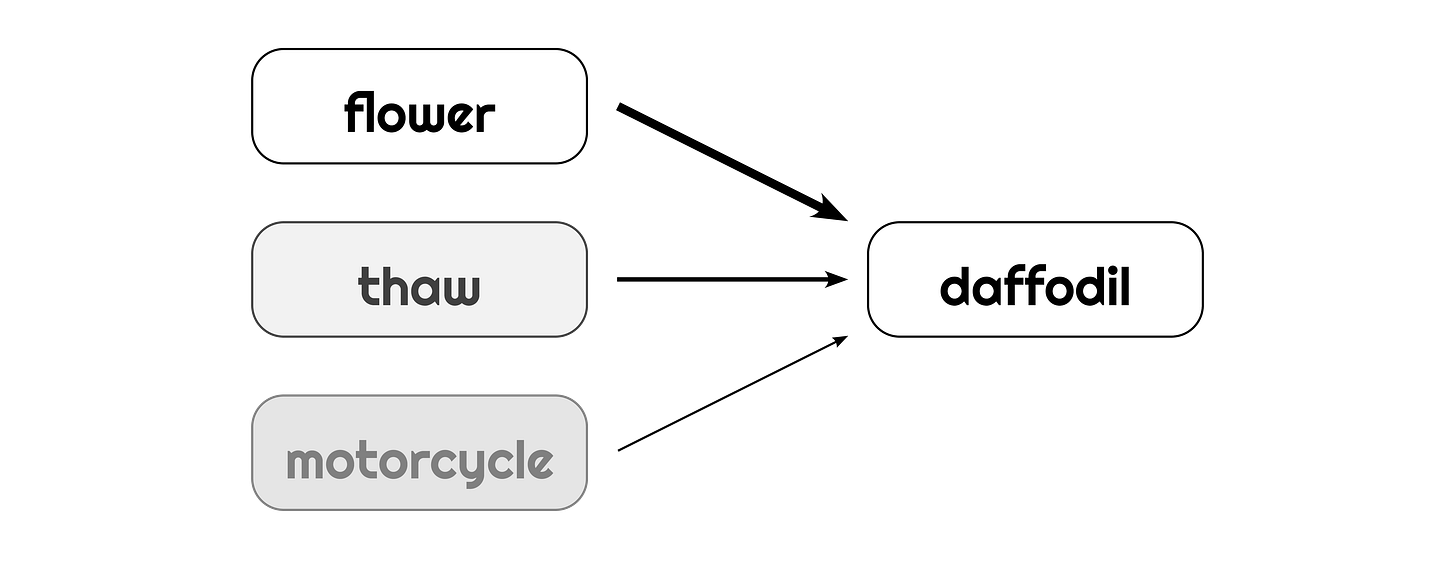

New science has shown that dreams have a particular predilection for novelty, favoring the exploration of weak associations over the strong, probable connections that rule the waking mind. Rather than predictably associating a library with books, the dreaming mind will instead conjure a library full of mangoes, or perhaps a daffodil that keeps telling you to shush, even though it’s the kids behind you that keep making all the noise. You never liked this daffodil anyway, and her lumpy green sweater makes her look like a troll. Does she know she’s got egg salad smeared across her face?

Anyway, this enthusiasm for weak associations is what makes dreams so bizarre.

In their book When Brains Dream, dream researchers Antonio Zadra and Robert Stickgold refer to this divergent form of memory processing as NEXTUP, or Network Exploration to Understand Possibilities. While we sleep, ideas are explored on a continuum of associative strength, in which strong associations are reinforced, weak associations are tested for potential utility, and novel associations are allowed to emerge through the exploratory linkage of isolated ideas. In the subterranean network of our minds, new connections are encouraged to take root.

This dance of neural pathways allows disparate concepts to blend and intertwine, leading to creative breakthroughs such as the periodic table or the structure of DNA. While the majority of dream content bypasses our conscious memory— preventing neural overload and confusion with reality—relevant associations are held within our implicit memory system. Working in the background, these unconscious insights aid in our ability to learn new ideas, solve tricky problems, and react to unexpected situations.

This adaptive cognition also helps regulate our emotions. Dreaming creates a safe, exploratory space to revisit difficult memories, free of conscious avoidance. Dreams work by recontextualizing those memories, bathing them in new associations and rehearsing novel forms of emotional response. Our instinctual response to fear or danger gets processed and decomposed, allowing painful memories to be reabsorbed into one’s broader emotional landscape. Beneath rich layers of insight bloom entirely new ways of being.

It’s dark again, and the chorus of chewing continues. I taste the sugar on my tongue and share it with those around me. They smile and offer thanks, but their voices are drowned out by the screech of the subway, rumbling through the bedrock above my head. When it finally fades, everyone is singing.

- dream journal, dec 28th

Assignment #3: Drink the Tea

Two weeks into the new year, I had my first lucid dream. I had woken up just before sunrise, and as I fumbled down the stairs in the dark, I wished that my apartment had had more windows. The kitchen wall suddenly folded in on itself, stretching into a greenhouse nearly a hundred feet long. I blinked my eyes and a row of tulips appeared—glowing like fireflies in the light of the dawn.

I’m skating on a pond under the moonlight. I can see every star reflected in the ice. The sun rises and the pond melts. I plunge into the heavens.

- dream journal, feb 12th

Most lucid dreaming happens in early morning, just as the stars are announcing last call. The prefrontal cortex will stir in its sleep, allowing self-awareness to slip past the threshold. Experienced dreamers know this crossing well, and often use plant medicines to help navigate the way. Teas brewed with mugwort support relaxation and dream recall, priming the neural pathways to induce lucid dreaming. Other popular oneirogens include blue lotus, calea, and galantamine—a chemical compound extracted from the bulbs of snowdrops.

Galantamine works by inhibiting the breakdown of acetylcholine in the brain—a neurotransmitter essential for focus and long-term memory storage. By sustaining levels of acetylcholine during and after REM sleep, galantamine aids in dream recall and conscious awareness. Its powerful effects on memory and attention make it a promising treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, slowing cholinergic decline and assisting with long-term recall. Produced by plants in the subfamily Amaryllidoideae, galantamine is typically harvested from snowdrops or their cousins—sigh—the daffodils.

Assignment #4: Sleep Upside Down

Why, when we speak of a new idea, do we conjure the image of a lightbulb? What a strange thing to call it: a light bulb. Like something out of a dream…

If insight is truly buried deep in the mind, then I suppose discovering it is an act of unearthing. It requires we do some digging around in the dark. Eventually you stumble upon something planted long ago, tucked between tree roots, waiting for spring.

Two years before his death, Charles Darwin wrote a book called The Power of Movement in Plants. Buried deep on the very last page is a remarkable hypothesis: a plant’s brain exists in its roots. Published in 1880, the book explores the ability of plants to search out and move toward resources in their environment. Having observed the power of root tips to gain awareness of their surroundings, Darwin came to see plants as an organism upside down: their heads rooted in the soil, their sexual and digestive organs (their flowers and leaves) waving in the air.

“It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the tip of the radicle thus endowed, and having the power of directing the movements of the adjoining parts, acts like the brain of one of the lower animals; the brain being seated within the anterior end of the body; receiving impressions from the sense-organs, and directing the [various] movements.”

The soil is where earth does most of its thinking. But it also serves as the foundation for human dreaming. Evolutionary anthropologists believe that it was our transition from arboreal to ground-dwelling species that unlocked the power of our dreams. By no longer needing to cling to the branches, our slumbering bodies relaxed into deeper patterns of sleep. This increase in REM cycles accelerated the adaptive cognition that dreaming supports, allowing humans to rehearse new behaviors and methods of cooperation.

If trees really do have brains like us, then what do they dream of as they sleep through the winter? What visions arise through those cycles of freeze and thaw? Much like us, their bodies lie still: concentrating resources and activity towards the brain. And while their towering limbs lie leafless and dormant, the roots of many species continue to explore—searching out new worlds and imagining future seasons. Under a safe blanket of soil they too begin to play, freed from the imperatives of a hot summer’s day.

While my neighbor’s tree is now nothing but a stump, her sprawling root system still remains. Perhaps she’s still there somehow, dreaming beneath the garden. What would you dream of on your last night of sleep? One of my dreams is to not be forgotten.

I read somewhere that the memory compounds in snowdrops evolved as a chemical reminder. Snowdrop bulbs are rather unpalatable and can induce nausea when ingested. Galantamine acts as a gentle teacher, reminding hungry animals to avoid digging there in the future, ensuring the bulbs can bloom every spring.

I’m still waiting for my own bulbs to pop, but it’s their first winter in the garden, so they’re a bit slow to wake. Buried deep between the roots of the oak, I hope they’ll carry her memory as well. I guess that’s why we plant bulbs for spring—to remind us what it feels like for things to be alive.

Until then, I will rely on that blasted daffodil. Despite my disdain, she is the oldest member of the garden, and the tree’s longest confidant. And with her mighty trumpet she spreads the dream: of what it feels like to reach toward the sky.

The stars 🌟 announcing last call - this line will stay with me for the rest of my life. And the dream of not being forgotten, and the roots as the brain of plants. So joyously grateful to stumble upon your piece this morning!

thanks for this lovely read. I was on one of the research teams that validated galantamine as a lucid dreaming aid. And one of our findings is that the compound seems to have a healing effect too. Poetically I apply this concept to your wonderful metaphor here for the spring as one not just of memory but of integration.