Hello readers! Welcome back to Unnatural Heritage. Today’s piece explores translucent bodies, prison technology, Y2K nostalgia, and the joys of being seen. Enjoy :)

Good morning, earthlings.

Before we begin: a quick celebration. Today marks one year of Unnatural Heritage! If you’re new here, welcome, I’m so happy to have you. To those who’ve been along for the ride, reading and commenting and sending me messages: thank you. I remember every message. You make me feel seen.

I started Unnatural Heritage to examine what felt like a growing gap between our natural and digital worlds. As a kid at the dawn of the internet, I never really noticed it. But as I grew further into each world, I realized they were increasingly placed in opposition to one another: the natural vs. the artificial, the physical vs. the immaterial, bounded constraints vs. limitless possibilities, the cure vs. the addiction. Why this great chasm? Who dug it, and why? The cuts in the earth look fresh to me. And the rocks are the same on either side.

The goal of Unnatural Heritage is to mend this gap—or at the very least, to mind it. You can read more about it on my website here. While the foundations of this division are economic and material, it’s the spiritual and conceptual distance we’ve created between worlds that cause them to compete for our attention. This is the realm that Unnatural Heritage tries to blur.

Today’s piece was inspired by the great social media exodus that’s currently unfolding, and is an attempt to process my own ambivalence in saying goodbye.

The TVs in Prison Bare Their Hearts

I have never been to prison. But the technology of my childhood primed me for what it would feel like.

The technology of the early 2000s was bulbous and bodied, shining its entrails through translucent plastic shells, heralding the new age in flecks of green and copper. Y2K product design was defined largely by the “clear craze”, which pronounced the new millennium by showcasing its digital nervous system. Circuitboards and wires became aesthetic objects in themselves: the organs of the 21st century, tiny and mysterious, electrons sparkling in the molecular sublime. Devices were becoming more complex, more exciting, more alive. Everyone wanted to see what was inside.

Before our first computer planted itself in the living room, I would fish for bullfrogs in the creek behind our house. I would crouch quietly along the bank with my bamboo pole, hovering a scrap of red oil rag above the chorus, waiting for one to leap. The big frogs never fell for it, but the smaller ones always did. They’d twirl like dancers as I pulled them from the stream, their long legs bent in a graceful plié. With a gentle squeeze I’d remove the hook, running my finger along the ridge behind their eyes. Some struggled, but most would just lie still. Perhaps they were happy to have their spots admired. Once, I caught a pregnant one: eggs jostling inside her milky, translucent belly. A thousand lives in the palm of my hand. It was more than I could handle. I set her back in the grass, and she instantly dissolved into ripples.

The desire to see inside our devices was originally conceived behind bars. The earliest clear devices were made for the criminal justice system—designed for easy inspection and to stop the flow of contraband being smuggled into prisons. Products like TVs and radios had strict manufacturing guidelines to ensure they could not be dissembled into makeshift weapons. Devices had to be cheap and lightweight, with clear plastic cases, sonically welded to avoid the use of screws. Technology—like most bodies in prison—was perceived as a threat. Perhaps on the outside we sensed this, too.

Clear products percolated into consumer markets throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, beginning with the release of Polaroid’s Sun 600 cameras in 1981. In 1983, Swatch released its iconic “Jellyfish” watch, with its silicone wristband and viscera of floating gears. The first clear device I remember owning was an Action Replay cartridge for my Game Boy. Essentially, it was a plug-in full of cheat codes. While I could never outsmart the biggest frog in our creek, the device allowed me to catch any Pokémon I wanted. Circuit boards could be hacked in ways that real life could not.

Eventually, I did catch the king of the bullfrogs. It was a sunny day in June, and I beamed barefoot as I pulled him from the creek, the bamboo pole bowing reverently in his presence. His legs were adorned with dark green stripes: a regal outfit for the emperor of the reeds. I kissed him gently on the top of his crown and pinched my fingers to remove the hook. Only it wouldn’t budge. It had lodged itself in the thick cartilage of his snout, and the slime on his back made it difficult to grasp. I tried a different angle, and a bead of blood pooled in the web of my fingers. I began to panic. Some hooks just don’t come out.

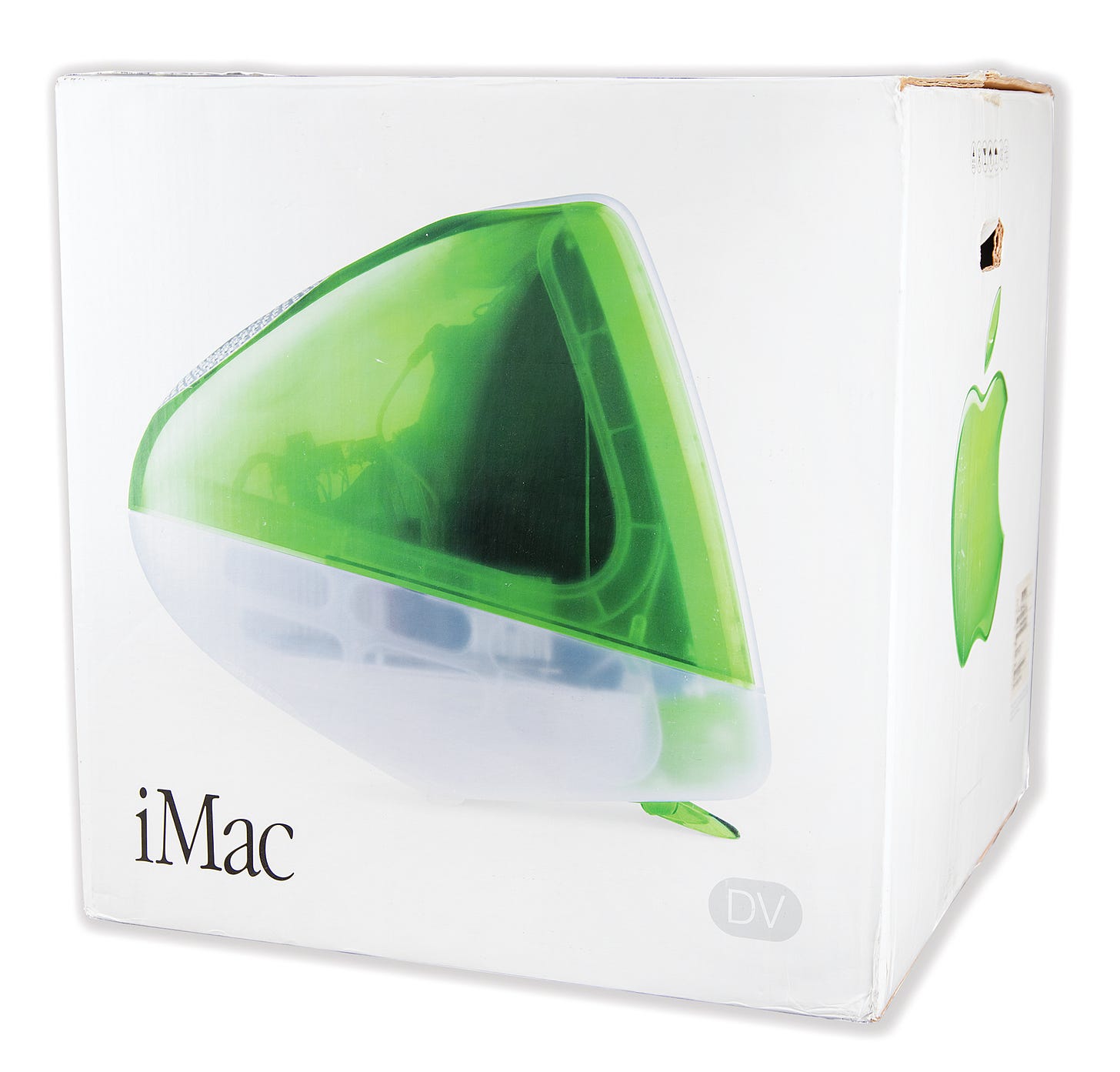

As the new millennium approached, product design got gooier, absorbing influences from the emerging blobitecture before dousing itself in Nickelodeon slime. The Y2K era saw a shift from clear transparency to poppy, colorful translucence: epitomized by Apple’s iMac G3, released in 1998. Inspired by the clear blue waters of Bondi Beach (a popular surfing spot in Australia), it ushered in a whole new wave of crystallaginous digital creatures.

Despite their alien auras, the blobjects of this era were endearing because, just like us, they had bodies. They had curves and circulatory systems, buttons and guts. The cathode ray tube—the central organ in the iMac’s visual display—was a long, cylindrical vacuum that required a deep carapace in order to protect it. When you looked through the iMac’s colorful shell, you could see it there, pulsing, shooting electrons at the phosphorus film behind the face of the screen. Devices back then had their own interior worlds, and through them and by example, we began to express our own.

Turning Inside Out

There’s an old myth that deals with boiling frogs. It states that most frogs, if thrown in a pot of boiling water, will jump out immediately. But when set in a pot of tepid water, then slowly brought to a boil, the frog won’t sense the danger until it’s already too late. I have no idea whether it’s actually true, but my friend Etienne says it’s better to fry them, anyway.

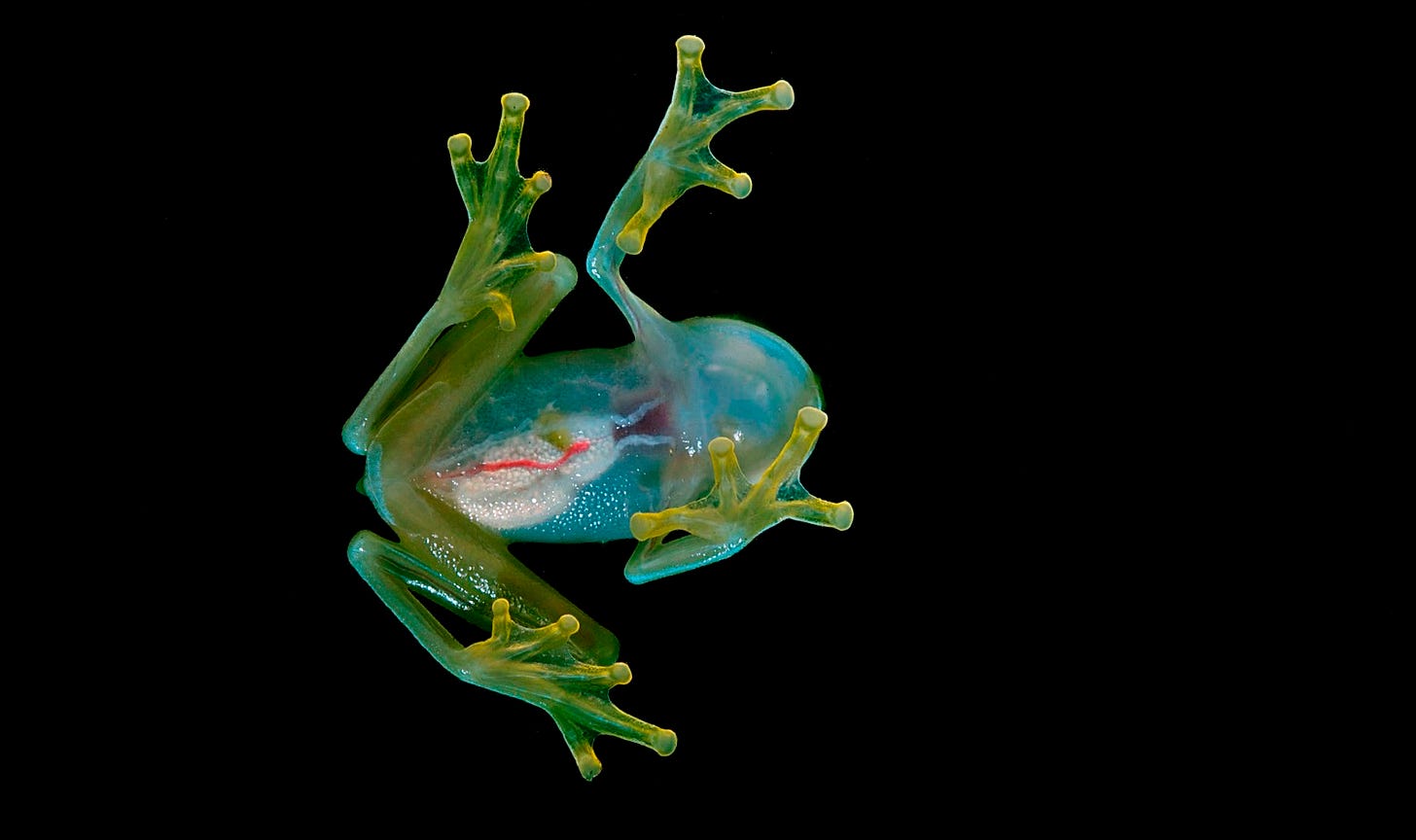

The watery world of the iMac was blobby and biomorphic, oozing around in the liminal space between our physical and virtual realms. The shape of that space had yet to solidify: its membrane was fluid and full of amphibious creatures. Amphibians, as you may know, were among the first creatures to make the pilgrimage onto land, and they remain our foremost experts in navigating between worlds. Their permeable skin assists them in breathing and makes them sensitive indicators of ecological health. When the city started dumping sewage into our creek, the frogs were the first to go.

The introduction of the liquid crystal display (LCD) marked a transformation toward something new. The bulky shells used to house cathode ray tubes were no longer necessary, and our devices evolved to become slim and flat, like a tapeworm. Their three-dimensional bodies were reduced to mere faces: a strange foreshadowing of the events to come.

Tapeworms, as it turns out, are some of the oldest parasites in the fossil record. Their primitive ancestors still lurk near the bottom of the ocean, dwelling in the stomachs of ancient chimaeras. Other inhabitants of this twilight zone include the elusive glass octopus, only recently captured on camera; and the barreleye fish, whose translucent skull allows it to look straight up through the water column in search of tiny crustaceans. I wonder if they ever feel nervous as they feed, knowing that predators can see inside their brains. Then again, everyone down there is just swimming around in the dark.

Back on land, things were heating up. The number of people communicating online skyrocketed through the 1990s following the launch of AOL Instant Messenger (1997), and catalyzed further by blogging platforms LiveJournal and Blogger (both 1999). MySpace, the first social media network to reach a global audience, launched in 2003. I shared a room with my sister at the time, and remember obsessively tweaking the background of my page—the only space in the whole world that was utterly and completely mine.

Millions of people began sharing their lives online, inspired by the possibilities for connection and self-expression. Distances collapsed, and the boundaries of the physical world grew delightfully porous. Humanity breathed into the space, lining its walls with the traces of ourselves. Over time, a familiar image began to appear—a digital doppelgänger, alive within the machine. I remember the excitement of peering into my device for the first time and seeing, not circuit boards or wires, but my own self staring back at me. He was someone I aspired to, and had worked hard to create. I dreamed that others might see him, too.

The heat of the moment steadily grew, and the watery world of the iMac slowly evaporated. To say it disappeared is to misunderstand the physics. Instead, technology vaporized—dissipating into a cloud of devices, volatilizing out into the cultural ether. It became the air we breathed. It got into our skin.

At some point, I realized that the image I had made for myself had begun to look like others. Personal aspirations and the dreams sold by advertising had been placed on the same substrate. Suddenly, everybody was a brand. Our behavior online became exhausting, and the exhaust from our behavior became its own renewable resource. It was mined for profit, and everywhere you went you could smell the fumes.

Underneath this new surveillance, we came to recognize the logic of the prison, turned inside out. Our devices had become more and more opaque, and it was us who were rendered see-through.

Letting the Light In

What is the cost of being seen? For most creatures, it’s a matter of life and death.

To evade their predators in the Costa Rican jungle, glass frogs have developed a remarkable strategy of concealment. Rather than covering themselves in a cloak of deceptive patterns, they simply let the light shine through. As nocturnal creatures who sleep during the day, they gather all their blood at the center of their liver, leaving the rest of their body completely transparent. Their edges blur in the bright viridescence of the leaves above them, and their frog-like shape becomes indiscernible to anyone lurking beneath. In the right light and against the proper backdrop, transparency can be a powerful form of camouflage.

I think the frogs have something to teach us about living in the world today. There are risks and rewards to baring your soul to the jungle. Still, I worry about disappearing altogether. By keeping things too close, do I risk becoming invisible? If I show too much of myself, if I let the wrong light in, do I risk having my contours become indiscernible, even to me? How does one stay porous but protected in this world? The answers feel hazy, translucent, not quite clear.

The issue of transparency is often burdened by questions of privacy, safety, or survival. Sometimes, though, it’s not about any of those things. For no evolutionary reason whatsoever, skeleton flowers become clear in the rain, simply from the joy of being watered.

This is an insanely informative video about the history of prison tech that’s absolutely worth watching. Highly recommend!

Dang. So well-written. And the photos are all stunning!

The world needs more essays like this: it's so bizarre and gorgeous, breaking down the boundaries between biology, technology, and millennial nostalgia writing...