This week’s newsletter is a reprint of an article I published in The Other Almanac: a reimagining of The Old Farmer’s Almanac for the era of climate change. The publication brings together climate organizers, indigenous activists, herbalists, farmworkers, historians, scientists, and more to share ancient wisdom and new approaches to thinking about the natural world. AND, they’re hiring a managing editor! If you know any New York-based folks who might be interested, please share this link to apply. As always, thanks for reading.

Good morning, earthlings.

The year I was born, my parents planted a pin oak in our yard—a symbol of new life and a gesture toward the future they hoped to create for me. Year after year, the tree and I grew alongside one another. Slowly we began to develop different attitudes towards the soil we were planted in. Like so many small-town queer kids, I grew up feeling stunted and choked by the inhospitable terrain around me. I kept my roots small and nimble, and when an opportunity finally presented itself, I picked them up and ran east. The oak tree, unable to follow, spread its roots deep and wide, eventually encircling the foundation of our home.

Such is the reality of arboreal life. Unable to move in the face of adverse conditions, trees have become masters of adaptation in place, regulating nutrient uptake and metabolism to survive dramatic fluctuations in their environment. This quiet intelligence allows trees to live hundreds of years in the same spot. The Alley Pond Giant—New York City’s oldest tree—was a sapling when the Dutch arrived. It’s the only living being to have witnessed the city’s development from the beginning. With my own feet now on fertile ground, I find wisdom in this steadfast commitment to place, consulting the trees on matters of patience and persistence. But to fixate too much on this quality of rootedness is to quite literally miss the forest for the trees. While a single oak may stand rooted in place, the forests, my friends, are running.

As a landscape architect in New York City, much of my work focuses on adapting our built environment to the challenges of climate change. As weather patterns begin to dramatically shift, many tree species are moving beyond their native ranges in an effort to keep up. In the eastern United States, hardwoods are moving west, while softwoods like pine and spruce are moving north. Ecosystems are being spliced and reshuffled, as old and familiar neighbors move in opposite directions.

For plant communities, migration is an intergenerational affair. Along the shores of every forest, mature trees cast their offspring outward to be carried by the winds or in the bellies of chirping songbirds. Each wave of young seedlings will eventually rise and crest, spilling more seeds outward and rising yet again. Movement is a communal ritual.

Forests have crept along in this rhythmic fashion, growing across generational tides, for millions of years. During North America’s last glacial retreat, pine and spruce trees swept the newly thawed landscape by upwards of a kilometer a year. Birch, maple, and beech soon followed. Through cycles of adaptation and competition, indigenous stewardship and settler-colonization, these species gradually became the forest communities we know today.

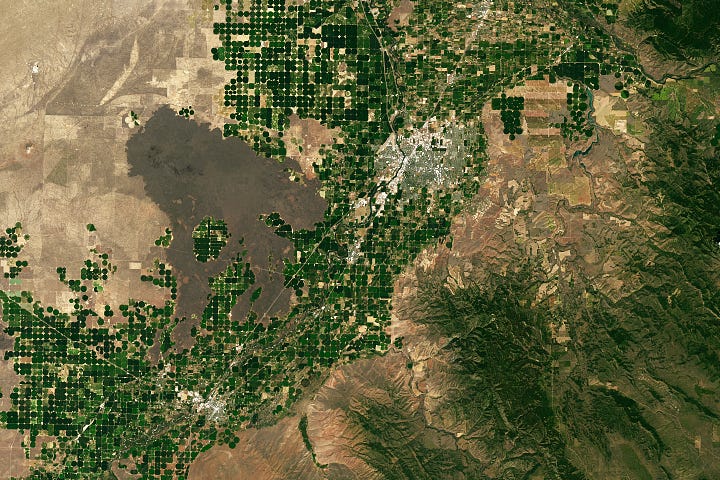

Our contemporary forests possess the same capacity to migrate in the face of climatic shifts, but they face an entirely new challenge: industrial development. Capitalist land use has deeply fragmented the mosaic of otherwise suitable habitat, with waves of young seedlings now crashing against the cliffs of vast agricultural fields and sprawling suburban development. In forest ecology, there is a term for this inhospitality: the outer seed shadow. In this zone, young seedlings fail to find fertile ground in proximity to their parents, falling victim to disturbances or environmental pressures and never reaching maturity. Such a fate haunts many human children as well.

For the future of our forests, these complications are the border walls. Certain species, due to their adaptability or seed dispersal method, are better than others at leaping over these walls. But many tree populations face a daunting future, effectively siloed within landscapes that will become too hot or dry for them to survive. As climate change accelerates, some species may not be able to keep up.

To save these vulnerable populations, ecologists have begun to advocate for the idea of “assisted migration”—proactively introducing species where future habitat conditions are projected to be more favorable. This intentional curation of plant communities echoes centuries of indigenous forest stewardship, and amounts to climate gardening on a regional scale.

Deliberately altering ecosystems carries both rewards and risks, so site selection is key. Growing evidence shows that urban forests—the rectilinear network of trees that braid together our parks and neighborhoods—may play a special role in supporting regional forests long-term. The density of paved surfaces causes cities to absorb more heat than their surroundings, producing a phenomena known as the urban heat island effect. When considering climate change, cities also become islands in time—places where climatic shifts are sped up and exacerbated. The cities of the Atlantic Seaboard represent an archipelago of the future—a string of portals by which to step into the climatic conditions of the coming century.

Our urban forests are at the forefront of climate change, presenting both challenges and opportunities. By replacing declining tree species with more southern-adapted selections, we can incubate early populations of climate-resilient trees in regions where winters are otherwise still too cold. As the rest of the region warms, new seedlings may find ground beyond the city, filling the niche of species that have migrated elsewhere.

Despite these potential advantages, the broad ecological implications of assisted migration leave a lot of questions. Will intentional introduction be helpful, or disruptive? The reality is that, as the climate warms, most ecosystems are in for a shake-up. Having made a home in New York, I will mourn the slow fade of black birch’s sweet scent, and the friendly shimmer of trembling aspen. Ecosystems are set to shift and reorganize, and new pairings of species will hybridize, outcompete, and coexist with one another. What strange new combinations might the future hold?

Urban forests offer a creative opportunity to consider this question. Already heavily curated by human hands, urban ecosystems exist as artificial compositions of species that would not naturally cohabitate. They’re one big garden—a living mosaic of a thousand tiny actions by communities to create a sense of place. As the climate changes and our cities transform around us, we must embrace the strange new worlds that become possible. Perhaps one day we will kayak through the bald cypress swamps of Staten Island, or picnic in the sourwood-magnolia groves in north Baltimore. What new places might begin to feel like home?

When I visit the tree my parents planted in our yard years ago, I wonder what kind of future they had envisioned. The pin oak, having never moved away, has grown much taller than me. Native to areas further south, it’s projected to do quite well in my home state over the next century. The future will carry stories that exceed our imaginations. In the gaps between reality and expectations, we may find the most fertile ground.

The 2024 edition of The Other Almanac, featuring contributions by adrienne marie brown, Bill McKibben, and myself(!), is available for purchase here.