Good morning, earthlings.

I recently watched an interview for Them in which Elliot Page was asked to divulge his earliest queer crushes. His first answer is a stunning deep cut: Amy Szalinski, the teenage daughter in the 1989 blockbuster Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. Played by actress Amy O’Neill, Amy Szalinski is a brand of effortless #coolgirl rarely found in the strict cheerleader vs. geek hierarchy of the 1980s. Popular but not a bitch about it, she makes burnt toast for her little brother and has a clear sense of life after high school, casually donning a loose striped overshirt, sleeves rolled up as she lip-syncs Nick Kamen into the mop handle. She’s a teenage prototype of the tough, sapphic heartthrobs that would define the ‘90s—Laura Dern in Jurassic Park or Helen Hunt in Twister. Talking on the phone with a friend, she smirks, “No, they broke up over religious differences. She thought she was God and he disagreed.”

In the interview, Page recounts his favorite scenes from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids—the characters riding a giant ant like a mechanical bull, or gorging themselves on an Oreo the size of a house—ultimately declaring the film a “cinematic masterpiece.” Six-year-old me would enthusiastically agree.

If you haven’t seen the movie, the plot is such: Hapless inventor Wayne Szalinski (played by Rick Moranis) is struggling to design a working shrink ray in the attic of his suburban home. Through a miracle of malfunction, the machine accidentally shrinks his two children and two of the neighbors’ kids while he’s away at work. Returning home after a humiliating presentation to funders, Szalinski takes a club to the machine, sweeping up its broken bits (along with his shrunken children) and placing them in a trash bag by the curb. To get back to the house, the kids must trek ₘᵢₗₑₛ across the backyard, facing one diminutive danger after another in hopes of being discovered by their parents. A pocket-sized pilgrimage ensues.

Conceived by comedy-horror duo Stuart Gordon and Brian Yuzna, the story was written as a kind of “Lovecraft for kids”—featuring giant bees, monstrous mushrooms, and snaking rivers of dog pee. A science safari gone awry, its perilous journey often mimics that of a war epic. The sounds of choppers overhead are revealed to be a giant monarch butterfly. The sprinkler system, accidentally turned on by a bumbling Rick Moranis, fires massive drops of water down on the children, exploding like missiles and almost drowning poor Amy.

Most importantly for our purposes, the film is an unforgettable entry into the canon of eco-horror. In my eyes, it is a phantasmagoric homage to one of the most unsettling creatures in the American psyche: the suburban lawn.

Much has been written about the ills of the American lawn. A playing field for our contemporary culture wars and a sinister symbol of racism and conformity, lawns are widely recognized as ecological nightmares. The “most common crop in America”, turfgrass devours enormous amounts of water, land, energy, and pesticides—while providing almost zero habitat value for local wildlife. Unwittingly or not, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids magnifies this ceaseless horror to stunning effect.

From the moment they slide down the first blade of grass, the characters must navigate a never-ending jungle of sameness. The few elements that break up the monotony—a flower, a mushroom, a Lego—become key landmarks on the journey, cinematic moments within themselves. And while the movie contains some impressive animatronic insects—bees, giant ants, a scorpion—in reality, the wildlife the characters encounter is conspicuously, ecologically, mercifully sparse. Thus lies the main lesson of the film: If you ever plan to shrink your children, it’s safer to dump them in an ecological desert than a hippy wildflower meadow.

My kids would be dead in seconds.

Despite a limited cast of insect interlocutors, the bug-centric scenes in the movie are stunning—an impressive mix of imagination and movie magic. Filmed in Mexico City, the film is a master class in set design and practical effects, requiring over 30 different miniaturized sets and utilizing a dazzling mix of stop-motion, puppetry, trick shots, and custom lenses. The result is an unforgettable depiction of survival from a bug’s point of view.

The cinema has given man an eye more marvelous than the multifaceted eye of the fly.

— Blaise Cendrars, “The Modern: A New Art, the Cinema”

In his 1934 book A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans: Picture Book of Invisible Worlds, Jakob von Uexküll introduced readers to a new concept: the Umwelt. As a biologist interested in the science of perception, von Uexküll sought to expand our understanding of the sensory world. He argued that animals, rather than being simple automatons, were intelligent creatures who navigated and altered the material world according to their own unique landscape of perception. This perceptual world—dictated by an organism’s size, environment, history, and physiology—was referred to as its Umwelt. His book introduced the Western world to the idea that the human body, while highly evolved and aided by technology, presents only one limited view of the world among many. In a bug’s eye lies hidden truths.

The openness to consider other modes of perception has profound implications for the ways we value the lives of others. In his book Ways of Being, James Bridle explains how gibbons were long thought to be less intelligent than other primates, consistently failing to use tools to reach food placed just beyond their enclosures. But gibbons are arboreal creatures: the moment the food was placed above their cages, they showed superior problem-solving skills. What earlier experiments failed to recognize is that a gibbon’s umwelt points upward, towards the canopy.

Among humans, we are finally re-embracing the perceptual intelligence and plasticity of differently-abled bodies and neurodivergent minds. By expanding our definition of “normal perception,” we open space for other sensory capacities to be sharpened in profound and powerful ways.

Von Uexküll’s writings, which inspired both poetry (Rilke) and phenomenology (Heidegger), maintain their relevance today, with new technologies offering us remarkable insight into animal vision and the sensory worlds of species like bees and butterflies. These studies—which deliver stunning images of compound eyes and UV-rendered flowers—are helping us to understand the harmful effects of light, noise, and electromagnetic pollution beyond our own perceptual realm.

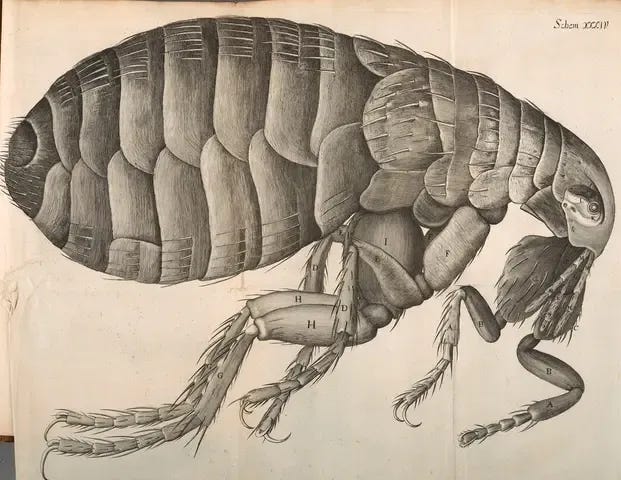

While the climate crisis demands that humans think bigger than themselves—across generations and continents and geological timescales—the benefits of thinking small may prove just as vital. Since Robert Hooke first introduced audiences to the wonder of microscopes in Micrographia (1665), we have gained remarkable insight into the tiny worlds of cells, microbes, and other diminutive lifeforms. As rapid insect decline destabilizes the foundations of our ecological and agricultural systems, the need to understand and care for these creatures becomes paramount to our own survival.

Thus lies the power of Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. While the film’s insects are—contrary to von Uexküll’s argument—purely mechanical, they were incredibly effective at opening this six-year-old’s eyes to the wonders of the non-human world. Kids already live in a world that’s too big for them—strange, otherworldly realms of perception are essentially the native territory. Only as adults do our minds and bodies become rigid.

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids set the stage for a procession of miniaturized kids films, including Fern Gully (1992), James and the Giant Peach (1996), The Borrowers (1997), Pixar’s A Bug’s Life (1998), and Dreamworks’ edgy rival flick, Antz (1998). All of these films invite us into an umwelt just beyond our own, reenchanting everyday objects and awakening empathy for the tiny beings with whom we share this world.

Science finds in the insect a world that is closed to us… their impassive exterior seems to denote complete indifference. Let us not insist too much: the private feelings of animals are an unfathomable mystery.

— J. Henri Fabre, The Life of the Grasshopper

To slumber in the soft nook of a flower, to dance wildly in its lush bed of pollen. To gorge oneself on house-sized cookies or roll a tiny bit of poop into a perfect sphere under the cosmic light of the Milky Way. These are the joys of a little life worth living.

RESIDENCY UPDATE

I am currently in residency at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, where I’m living my own suburban fantasy: drowsily making coffee in a giant kitchen, surrounded by a lawn that spills out for days. I bought a macro lens for my iPhone and have been capturing the tiny worlds around me.

I hope you enjoy them!